Fantasy Middle Ages: the snake and the dragon

The snake and the dragon is a very complex figure also from a symbolic point of view. For this reason, here we will address some aspects without claiming to cover the entire topic.

Let’s start by saying that it’s often not easy to distinguish the snake from the dragon and other similar monsters in Romanesque iconography. From an iconographic point of view, the dragon was only codified at the end of the Middle Ages.

The dragon plays a fundamental role in the Apocalypse of John. Opposed to God, it appears in particular in chapters 12 and 13. In 12:17, where we see it grappling with the woman in labour, Michael and ‘those who keep the commandments of God and bear testimony to Jesus’. In this context the dragon is the image of the force of evil, so much so that he is able to confer ‘power’ and ‘great authority’ on the beast that came from the sea, or rather on political power (Revelation 13,2-4). One almost has the impression, in this passage, of being faced with an influence of Manichaeism, given that it would seem to attribute to evil the same power as the forces of good.

However, of the beast that comes out of the earth and has horns similar to those of the Lamb, John says (Revelation 13,11) that it ‘spoke like a dragon’. And this is the typical dissimulation of the Antichrist.

The snake has always struck the collective imagination, especially in the agricultural world, given its prevalence in the countryside. The fact that it disappears completely into its hole has led to its association with the earth and the underworld. It was also said to have the ability to cast a spell with its gaze.

Furthermore, since it was said to have been born from an egg, the snake was associated with birds. This is why we often see it depicted with wings, just like the dragon.

It was a source of wonder that the snake periodically shed its skin and immediately grew a new one. It thus became a symbol of life renewing itself and of the continuity of existence.

Tertullian, referring to classical naturalists, stated that the snake had the ability not only to shed its skin but also to change its age. According to Tertullian, when this animal felt old, it would get itself stuck in a narrow passage and, by flaying itself, would come out with a new skin and feeling rejuvenated. The snake thus became the symbol of time renewing itself and also of life.

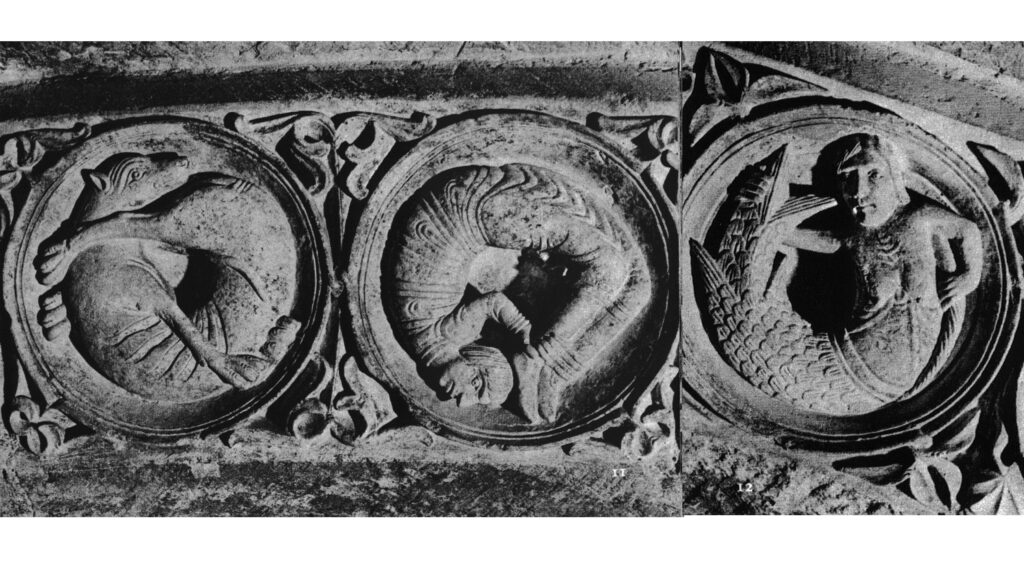

The symbol of the renewal of life and the cyclical repetition of time is the ouroboros, the snake (or dragon) that bites its own tail. It is a very ancient symbol, as we find it already in ancient Egypt in the form of a bracelet, for example. And in the Middle Ages, with its body becoming a circle, we find the ouroboros often depicted in miniatures.

It was believed that the ouroboros, similar to a lizard, had the ability to recover its lost tail. It was also widely believed that the ouroboros, by folding in on itself and sucking its own tail, found its vital forces. In this very thing was a vital principle which, once absorbed, would allow the creature to regenerate. This explains the meaning of the ouroboros symbol in alchemy texts.

The ouroboros snake principle is found in many other beings depicted biting their tails.

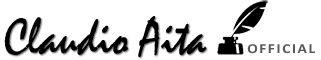

An echo can also be found in the depictions of figures portrayed in the shape of a coil, as in the case of the dog, the man and the serene woman in the medallions of the Vézelay portal.

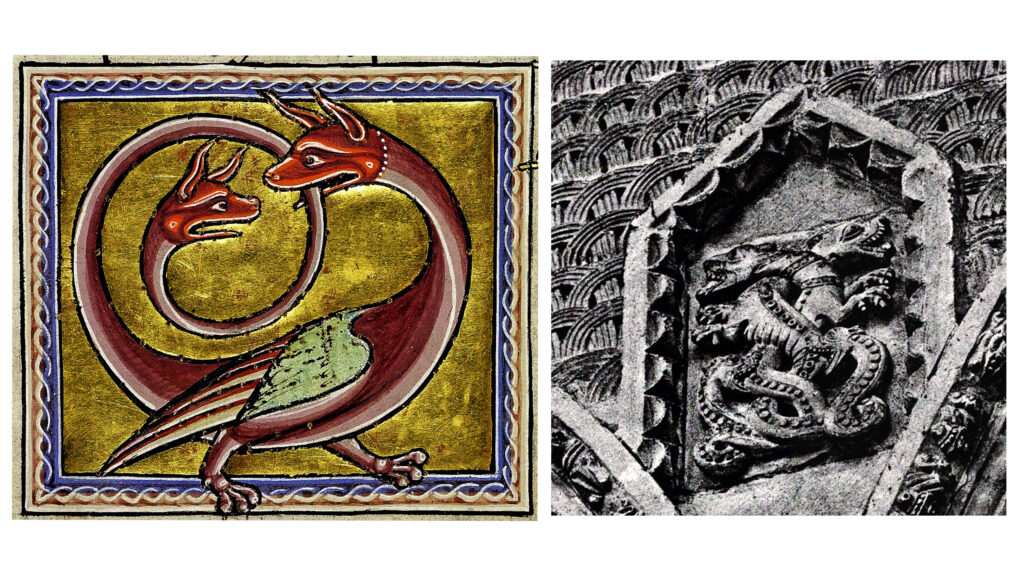

Similar to the ouroboros is the amphisbaena, which is a snake with two heads at its ends. Pliny, from whom medieval commentators drew, was certain of its existence. Brunetto Latini, Dante’s teacher, wrote that ‘Anfismenia is a kind of serpent that has two heads: one in its place and the other in its tail, and it can bite on either side, and it runs nimbly, and its eyes are as bright as candles’.

A knot made by the intersection of two snake-heads can be seen inside the cathedral of Bayeux.

Sometimes we find the snake represented in the form of a spiral. The spiral is movement, albeit relative, unlike the circle whose movement is never-ending.

The spiral is sometimes found on the crosiers of bishops and abbots, where it ends with the representation of a snake or a dragon. The reason for this unusual representation can be found in some biblical passages which, in the medieval imagination, led to the image of the snake being assimilated even to the figure of Christ.

The Christ-serpent is particularly inspired by the biblical story in which the pharaoh asks Moses and Aaron for a miracle. The latter, on the Lord’s orders, throws his staff at the feet of the sovereign and it turns into a snake.

“Moses and Aaron came to Pharaoh and did as the Lord had commanded. Aronne threw his stick in front of the Pharaoh and his servants, and it became a snake.

But the Pharaoh also called wise men and enchanters, and the magicians of Egypt did the same with their spells. Each threw their stick which became a snake, but Aaron’s stick swallowed their sticks.

(Exodus 7,10-12)

Here Christian exegetes have interpreted this as symbolising Christ who, dying on the cross, is victorious over our sins and evil.

A second passage is Matthew 10,16:

‘Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves; so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves’.

And this explains the simultaneous presence of the two animals, snake and dove, for example, in the ivory crosier of Sant’Annone, kept in Siegburg, Germany, in which the dove is above the head of the snake. And this is obviously why the snake is often depicted to symbolise the virtue of patience.

It should be noted that, although the crosier is a very ancient emblem, it was the Irish Celts who associated it with the figure of the bishop and used the symbol of the spiral, also typically Celtic, for them.

Similar to croziers are the ‘tau’ staffs that preceded the croziers properly speaking and that are decorated with spirals on the ivory top. Their shape is inspired by the ‘tau’ sign traced by the prophet Ezekiel on the foreheads of the Jews. A sign in which the Fathers wanted to see a representation of the Trinity and, above all, a prefiguration of the cross of Christ.

Here we see a beautiful example from Jumieges, now in the Rouen museum. The figure in the centre is an abbot. We recognise this because he is holding his crosier towards himself (if it had been a bishop, it would have been the other way round). This is the direction of self-sacrifice and mortification. Here too we see the beast on one side and the lamb on the other, with the victim, on the right, enclosed by a double interweaving that repeats the direction of the crozier in the hand of the abbot in the centre.

This, on the other hand, is a 13th century Italian pastoral cross whose staff ends with the head of a dragon with two horns, a symbol of death, which with its open mouth threatens the lamb-Christ, whose head is turned backwards in opposition. Note the three appendages of the banner that the Lamb holds with his paw, representing the three days that Jesus spent in the sepulchre.

In chapter XXI of the book of Numbers we read that the Lord, to punish the Israelites who complained against Moses and God, ‘sent fiery serpents among the people and they bit the people so that many of them died’.

Repentant, they ask Moses to intercede. At God’s request:

‘Moses made a bronze serpent and put it on a pole; if a snake bit someone, and they looked at the bronze serpent, they lived’.

(Numbers 21,9)

In this case, Jesus himself will be equated with the symbol of Moses’ snake:

‘Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the desert, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life.’

(John 3,14-15)

Therefore, it was natural to compare the snake to Christ, who heals us from the snake’s bite, or in other words, from evil.

It must be said that the Fathers often expressed caution in identifying the figure of the snake with that of Christ, while certain Gnostic circles went so far as to worship the snake as such. This hesitation also derived from the assimilation of the snake with sin.

For example, St Thomas Aquinas, commenting on the verse in John, feels obliged to specify that:

‘The bronze serpent had the form of a snake, but not its venom. So Christ, perfectly innocent, did not want to be thought to have the appearance of sin’.

Perhaps it is because of this ambiguity and the danger that superstitions would arise from such an enigmatic animal that medieval artists hesitated to reproduce the theme of Moses and the snake on the stone. And even Moses is normally depicted in other ways.

However, there is a famous representation of Moses’ snake and it can be found in the basilica of Sant’Ambrogio in Milan. It is an ancient snake that was probably once a symbol of Aesculapius and was even a gift from a Byzantine emperor. Hence the belief, in the past, that it was the bronze serpent of Moses, so much so that for centuries the Milanese attributed miraculous powers to it. In short, further evidence to avoid representations of Moses with the serpent.

As we saw in another text about the lion, in many traditions the snake takes on the role of guardian of the sacred place. Or, in particular, of the tree. It prevents man from approaching it or drives him away after tempting him to sin.

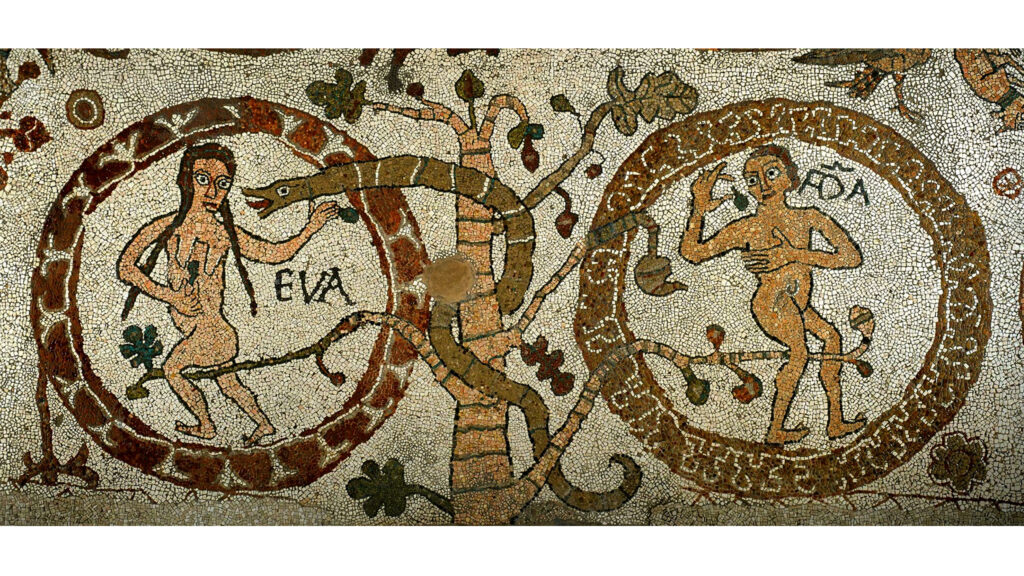

This is the case of the story of Adam and Eve narrated in Genesis 3,1.2.4.13.14. It must be said that, in this case, the association between the tempting serpent of Genesis and Satan is very late. It is an interpretation that will be suggested, in the biblical context, by the text of Wisdom. This interpretation was subsequently adopted by the whole of Christian tradition. It is no coincidence that the Book of Revelation refers to Satan as the ‘ancient serpent’ (Revelation 12,9 and 20,2).

In chapter 12 of the Apocalypse of John, we find the vision of the pregnant woman about to give birth, clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars around her head (Rev 12:1).

In front of her stands

‘[…] a bright red dragon with seven heads and ten horns, and on his heads were blazing eyes, and he had seven diadems on his heads. His tail swept a third of the stars of the sky and cast them to the earth’

(Revelation 12,3-4)

Later John explains that the great dragon is

‘[…] the ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world. He was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him.’

(Revelation 12:9)

Returning to the figure of the guardian of the sacred place, man cannot access the tree or the divine object and what it represents without a hard fight against mysterious and evil forces. Hercules, in order to take possession of the golden apples in the garden of the Hesperides, has to face a monster, just as Jason, in order to take possession of the golden fleece, is forced to kill a dragon.

Snakes also guard the symbols that embody the sacred and knowledge, as well as the path to immortality and the treasures of the gods. This is another reason why, in the popular imagination, it is often a snake that guards a treasure.

Medieval art often depicted the serpent tempting our ancestors next to the tree of the Garden of Eden. And we often see it depicted in a vertical position, as if to symbolise the sin of pride with its erect position, and the desire to claim God’s privileges for itself. This is why it led to the rebellion and downfall of Lucifer’s angels.

In any case, the snake is considered the repository of a superior wisdom, received from above. Since it has the ability to offer it, or at least that’s what it makes people believe, it possesses a great capacity for seduction.

The snake tempts to the point of provoking sin in a still innocent being, as happens to Adam and Eve.

In a capital of the church of Notre Dame de Moirax we see the two progenitors taking the fruit and, as soon as they realise they have sinned, they cover their nakedness with leaves. But next to them, on both complementary sides, Michael is depicted as he crushes the dragon. Death and evil, introduced by the demonic serpent, will not last forever.

Also for this reason, even if the snake, as in the case of Moses’, continues to have positive aspects, in medieval art it maintains a negative meaning.

In a capital in the church of San Isidoro in Léon (Spain), Lust is depicted with the features of a person bitten on the head and chest by four snakes.

An even more explicit representation is found in the portico of the abbey of Saint-Pierre in Moissac where we see a woman with toads and snakes devouring her breasts and genitals.

More ambiguous is the figure of the dragon that, although associated with the devil in the Apocalypse of John, is sometimes found alongside characters who are portrayed in an ascending pose and, therefore, facing the sky.

This is clearly the case in the praying man by Rozier-Côtes d’Aurec, in France, portrayed as he is ascending towards the sky, with his legs now detached from the ground and, therefore, from materiality.

L’uomo trasportato in cielo da dei dragoni si ritrova con ancora maggiore chiarezza, per citare un altro esempio, in un altro capitello. Qui l’essere, con lo sguardo ormai distaccato dal mondo, si aggrappa a dei draghi che hanno la coda tripartita, e il tre è il simbolo del cielo.