Fantasy Middle Ages: the lamb, sacrificial animal and triumphant creature

The lamb, together with the sheep and the ram, is one of the main symbols of Christian art and was already extremely widespread in the early days of Christianity when, in times of persecution, the first Christians preferred to use symbols representing Christ in a way that only the initiated could interpret.

Such is the case of the Good Shepherd who is depicted bringing the lost sheep back to the fold on his shoulders, as narrated in the Gospel of Luke (15, 5) or surrounded by his flock.

On the other hand, it was Jesus himself who defined himself in this way: I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep (John 10, 11). And a little further on: I lay down my life for the sheep. And I have other sheep that do not belong to this fold. These also I must lead, and they will listen to my voice, and they will become one flock, one shepherd (John 10, 15-16).

Here are two examples of this representation. The first is a 4th century engraving, now in the museum of the Baths of Diocletian, which represents the Good Shepherd, in the iconography that still saw Jesus without a beard. The second is a 5th century mosaic found in the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, in Ravenna. Here the context is more recent and Jesus is much more recognisable with the cross in his hand and a halo around his head. He is also associated with the source of living water mentioned in the Gospel of John.

These images evoke the peace promised to those who have been redeemed and who live in Christ. The baptised of the early centuries knew very well that death was only a passage to the place of peace while awaiting the resurrection.

But Christ is also the sacrificial lamb, thus recalling the figure of the paschal lamb sacrificed on the occasion of the exodus from Egypt and later eaten by the Jews every year. From this point of view, it also recalls the sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham, where the ram takes the place of his son Isaac, an event that reminds men of the certainty of God’s constant help.

When John the Baptist sees Jesus for the first time, he exclaims: ‘Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world’ (John 1, 29).

The Fathers of the Church wanted to see a relationship between the sacrifice of Isaac and that of Christ. We sometimes see this represented in Romanesque art, as in the tympanum of the church of Saint Isidore in Leon, Spain, where the biblical event is depicted in all its details at the bottom, and above, exactly above the figure of Abraham about to sacrifice his only son, there is a lamb carrying the cross and facing, as we shall soon see, in the direction of the sacrifice.

It should also be said that Christians have always seen the story of Jesus in the words of the prophets, such as Isaiah (53, 7): He was oppressed and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb led to the slaughter. Or Jeremiah (11, 19): I was like a gentle lamb led to the slaughter.

Not that the association between lamb and sacrifice was something new. It was a concept already used by the Jewish world (think of the Easter lamb) but more generally it was well known also in the Phoenician and Semitic context to which the Jews, after all, belonged. Suffice it to mention the much-discussed molk sacrifice celebrated in the Phoenician area and also, it seems now certain, in the Palestinian area and even in Jerusalem itself. In archaeological excavations, burnt bones of sacrificed lambs are often found together with the bodies of children or, later, instead of them.

Be that as it may, at a popular level, Christians have often wanted to represent the crucified Christ in the form of a lamb, a devotion against which various councils from the 6th to the 10th centuries took a stand. Without much success, if this type of representation is still found in Romanesque art, as can be seen on the back of the silver Cross of Monjardín, in Navarre, made in a period not much better defined between the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 13th century, and which is impressive for its dramatic effect. On the front of the cross we have the suffering image of Christ; if we look at the mirror behind it, we notice that on the back, at the intersection of the arms, the sacrificial lamb is represented, as if to emphasise the equivalence of the two figures.

This equivalence can even become a substitution, as we can see in the fragment of a cross with a disc in the centre bearing the image of a lamb, from the 12th century Civic Museum of the Middle Ages in Bologna.

But the lamb is also the being who, in the Apocalypse of John, is the only one capable of breaking the seven seals that close the book and reading its contents.

I saw a Lamb, standing at the centre of the throne, with the four living creatures and the elders; the Lamb had the seven horns of God’s seven Spirits and as many eyes as the seven Spirits. He came forward to take the scroll from the right hand of him who sat on the throne (Revelation 5, 6-7).

This image was widely reproduced in the form of miniatures, but we also find it painted in churches, as in the image on the vault of the crypt of the cathedral of Anagni (late 12th-early 13th century).

In the Apocalypse of John, the Lamb is also the animal of the Heavenly Jerusalem, the city of salvation and revelation now fulfilled.

In fact, the Book of Revelation says:

And the city had no need of the sun or of the moon to shine in it, for the glory of God illuminated it. The Lamb is its light.

(Revelation 21, 23)

and immediately after:

Only those written in the Lamb’s book of life could enter.

(Revelation 21, 27)

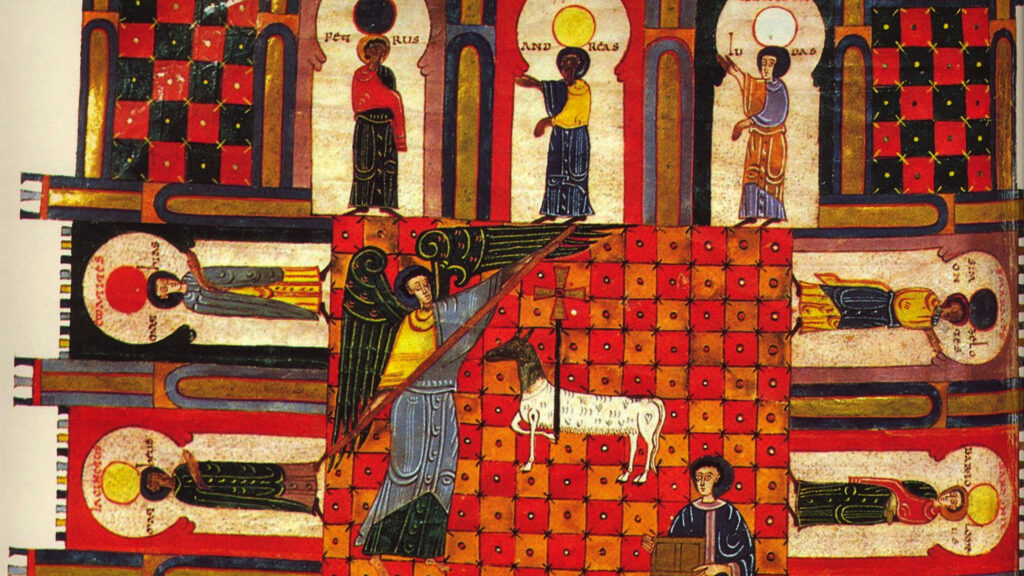

For this reason, in illuminated manuscripts, including the very colourful ones known as Beatus manuscripts and elsewhere, the Lamb is depicted inside the heavenly Jerusalem, as in the case of this Beatus manuscript kept in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid.

This symbolic role of the lamb as the one who illuminates the holy city explains some Romanesque representations, such as the tribune of the priory of Serrabone, in the French Pyrenees, where the figure of the lamb is inserted inside a circular sunburst.

For the same reason we often find the lamb holding the book or the cross represented in the keystone or on the top of the tympanum of Romanesque churches. Such is the case, for example, of the abbey of Charlieu, in central France, with this animal placed in a dominant position over the portal. It is worth remembering that the 24 circles on which the Lamb sits represent the 24 elders mentioned in the Apocalypse.

Or on the tympanum of the ancient 12th century abbey church of Rheinau, on the border between Switzerland and Germany, now located in the baroque tower of the current building.

Finally, we should note that medieval representations of the Lamb sometimes emphasise its symbolism as a sacrifice, as a victim, and others its apocalyptic glory. In the first case it is shown facing left, sometimes kneeling in an attitude of submission. In the second verse, he is on the right. We must remember that in the Middle Ages the concept of right and left, as we see in churches, had its own significance and was associated with positive or negative values. Churches, normally oriented from west to east, have a more positive side, the southern side associated with the south and the sun, and a more negative side, associated with the north and the dangers derived from evil and the devil. It is no coincidence that baptismal fonts are usually placed on the left side of the entrance, almost as a bulwark against the Evil One.

Returning to the Lamb, we can see that in the example of Serrabonne that we have already seen, the animal is facing right. As is the one in Charlieu.

On the other hand, the Lamb on the southern tympanum of the church of Sant’isidoro in Leon, Spain, is facing left. Its sacrificial significance is made clear by the association with Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac, which we have already discussed. The same is true of the very expressive one in Barcelona from San Pedro de Roda in Barcelona, now kept at the Marès Museum.

However, the times of the sacrifice of the Lamb-Christ and his glorious return are not always separate. And in fact the Lamb is frequently depicted with his head turned backwards, thus breaking the orientation of the body.

We can see this very clearly, for example, in the tympanum of the church of Saint-Pierre-aux-Liens in Varennes-l’Arconce, where the sacrificial lamb is depicted on its knees looking back at the cross of glory that stands out on its back.

The same scheme that we see depicted at Notre-Dame in Girolles and at Rheinau, as we have already had occasion to see.