Fantastic Middle Ages: the lion

The lion is not only one of the most constant presences in Romanesque iconography, but it is certainly one of the most complex and difficult to interpret. Its nature is not only ambivalent but sometimes even appears contrasting. It can symbolise Christ and the Church, but is also associated with the devil; it is a symbol of strength and violence, but the Bible also emphasises its weakness; its morality is celebrated but it is also used to symbolise lust; it is a sign of resurrection, but also of violence and death. In short, opposing concepts coexist in the lion and it is not always easy to understand which one the medieval artist or illustrator is referring to.

It is interesting to note that, since the first centuries of our era, the lion has been attributed a statistically remarkable importance, decidedly unusual compared to the models available to European artists. Among these, probably the consular diptychs in ivory that were still kept in church treasuries, and the Roman sarcophagi that sometimes depicted lion hunting scenes.

Here it is depicted, for example, in a sarcophagus from the 3rd century AD, on the left. Or in an ivory from the 6th century, on the right.

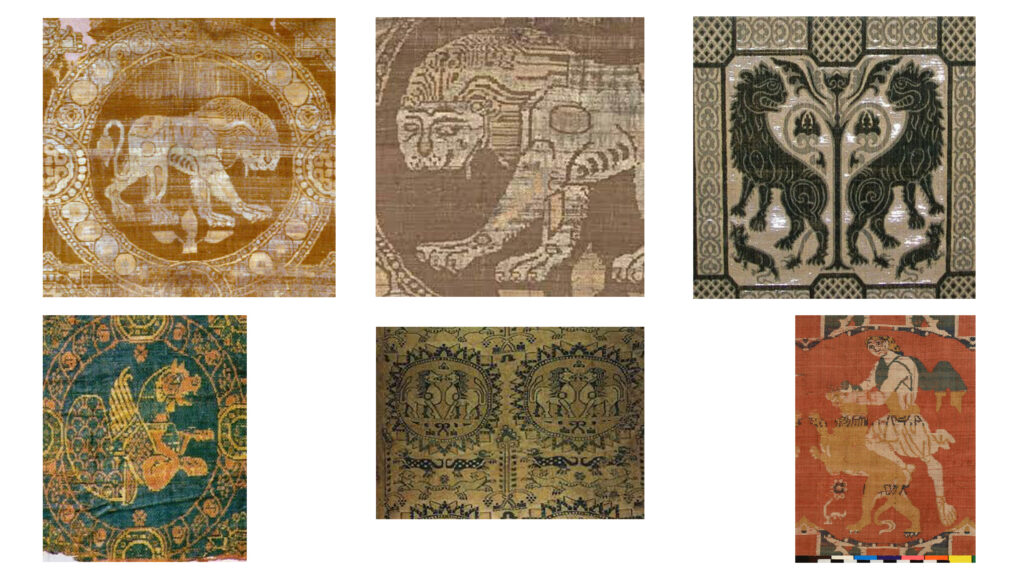

We mustn’t ignore Sasanian, Byzantine and Coptic textiles, which were also very widespread in the West.

In the figure we show some examples.

Furthermore, lions could still be seen alive in menageries, mostly royal and princely, where they were exhibited as a sign of power. Medieval Florence, at least until the plague of the mid-fourteenth century, even kept about thirty of these animals in a menagerie near Palazzo Vecchio, so much so that the lion, the ‘Marzocco’, is still one of the symbols of the city. And then there were the animal trainers who travelled to fairs and markets to exhibit, among other animals such as bears, sometimes even a lion or two. Therefore, it wasn’t difficult for some artist to have seen one of these animals in the flesh and to have had the opportunity to portray it.

However, this presence does not explain the lion’s predominance, so much so that this animal can be defined as the ‘star’ of the medieval bestiary. In miniatures and sculptures, for example, it is found everywhere. But, starting from the 12th century, it is also the figure that predominates unchallenged in heraldry. It is in fact represented on 15% of medieval coats of arms, which is a very high percentage if we consider that the figure that comes second, the band, doesn’t reach 6% and that the eagle, the only rival of the lion in heraldic bestiaries, doesn’t exceed 3%.

In medieval art, the lion is seen above all in its beneficial aspect, so much so that it appears in the Tetramorph as a symbol of the evangelist Mark. This is explained by the fact that this gospel begins by presenting John the Baptist with a quote from the prophet Isaiah:

‘Behold, I send my messenger ahead of you;

he will prepare your way

the voice of one crying out in the desert.’(Mark 1,3)

And in the desert, including the current Middle East, the lion lived.

The Fathers of the Church (St Hilary, St Augustine), following in the footsteps of Plutarch, claimed that this animal slept with its eyes always open, and it was believed that its young were also born with their eyes wide open. For this reason medieval exegetes used the lion as a stand-in for Christ in the sepulchre, seeing as open eyes are proof of Jesus’ divinity that manifests itself, while death testifies to his humanity.

But other authors also made this animal the symbol of the resurrection. Origen and Isidore of Seville wrote that lion cubs were born dead, but that the father would blow into their throats after three days to revive them. This made the lion a symbol of Christ himself. Although he appreciated its moral value, Saint Augustine admitted that this narrative was baseless.

RESURRECTION

A symbol of resurrection, the Lion is depicted on a capital of the church of Saint-Vincent in Chalon-sur-Saône (France) as he pulls apart the two branches of the Y-shaped tree that symbolises the choice between good and evil and the final judgement. One of the two branches leads to perdition, while the other leads to salvation. The tree symbolises above all the tree of life, from whose wood the cross will be made; in this case it is replaced by the figure of the lion.

It is therefore not surprising to see lions taking care of the burial of Egyptian ascetics and saints, in short, of men who in life already deserved eternal salvation for their merits. Such is the case of the Vézelay capital where two lions together with Saint Anthony the Abbot take care of the preparation of the tomb of Saint Paul the Hermit. The same subject is repeated on a capital in the basilica of Notre-Dame in Beaune but, in this case, there is only one lion.

In any case, because of its open eyes, the lion symbolised vigilance and justice. This is why it is often represented in the portals of Romanesque churches. In medieval bestiaries it was said that the lion is just because it never attacks an enemy that has fallen to the ground. Curiously, the same bestiaries, which referred to the descriptions of the most ancient naturalists, claimed that the lion was just because it severely punished its adulterous mate, especially when she gave herself to the pardo, an animal mentioned by the Vulgate of St. Jerome and Pliny the Elder, indicating the male panther. The fruit of this betrayal, with a play on words, was the ‘leopard’.

The lion, due to its power and its qualities, has always struck the imagination of human beings, since the most remote antiquity. So much so that it has become, even in classic fables, the king of animals. But this makes it similar to man who is at the top of creation. This is also why in many mythologies heroes cannot have a more worthy adversary than the lion. From Hercules to Gilgamesh. Without forgetting the story of Daniel in the lions‘ den.

In the image, a remarkable capital carved by the master of Cabestany in Sant’Antimo and representing Daniel in the lions’ den.

Due to this dominant position, the Lion occupies a prominent position in the Tetramorph, at the bottom left. We see it, for example, in miniatures such as that of the Book of Kells from the 8th century, illuminated by Irish monks, on the left. Or in the portals of Romanesque churches such as that of the cathedral of Le Mans, on the right, where the lion is the only animal to look so frankly at the face of Christ. The lion is counterbalanced by the eagle, top right, which is however the symbol of ascension.

DOUBLE LIONS

Lions are often depicted in pairs, as symbols of resurrection, and therefore of God’s love, and of strength. Lions in pairs are also symbols of justice, and also indicate the dual attitude of Christ who was, as St Jerome said, ‘benevolent to the good and implacable to the wicked’.

This ambiguity of the figure of the lion originates from the Bible itself, where we often find the lion mentioned as a symbol of justice. We find lions in pairs as symbols of strength and guardians of royal power in the description of Solomon’s throne (I Kings 10, 18-20):

The king also had an ivory throne made and overlaid it with fine gold. It had six steps, with a bull’s head at each step and a lion at each of the two side supports. There were twelve lions on the steps, six on this side and six on the other.

It is interesting to note that the iconography of the king seated on lions was also adopted in the representation of King David, who is sometimes depicted seated on two crossed lions, as can be seen on the doorjamb of the Miégeville door of the church of Saint-Sernin in Toulouse.

STRENGTH, WEAKNESS AND SATAN

The strength of the Lion is already mentioned in Genesis (49, 9-10) in the blessing of Judah by his father Jacob:

Judah is a lion’s whelp:

from the prey, my son, thou art gone up:

he stooped down, he couched as a lion,

and as an old lion; who shall rouse him up?

In contrast to the strength of the Lion, the same Bible describes its weakness, especially when it finds itself succumbing to man. Such is the case of the Timnah lion that Samson kills with extreme ease:

‘So Samson went down to Timnah with his father and his mother, and stayed there at the vineyards of Timnah. And a lion came roaring toward him. But he was filled with the Spirit of the Lord, and without hands the lion was torn to pieces as one might tear a young goat.’

(Judges 14,5-6)

In relation to Samson’s fight with the lion, sometimes we find the man attacking the animal from behind, grabbing its jaws from behind. As in the case of this capital from the church of Anzy-le-Duc.

This image can be linked to the double aspect of the lion, weak and mean in the rear part of the body and powerful in the chest.

And who could forget Daniel’s words to King Darius after the latter discovered that Daniel had been thrown into the lions‘ den but the animals hadn’t touched him: ’My God sent his angel to shut the lions‘ mouths, and they have not hurt me’.

(Daniel 6,23)

The figure of the lion, symbol of Christ, is also associated with Satan:

‘Be sober and vigilant; because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour’

(First Epistle of Peter 5:8)

The lion is also the symbol of revelation. We find it in the Apocalypse of John, as well as in the Tetramorph, as the only being worthy of opening the book, like the Lamb. The association of the lion with the lamb is sometimes found in the portals of Romanesque churches.

Here is an example of a lion column bearer, or rather a lion holding up a column on the façade of the Collegiate Church of San Quirico d’Orcia, in the Siena area. In his arms he holds a lamb, almost as if to protect it.

And here is the passage from the Book of Revelation that associates the two animals.

‘Do not weep! See, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so as to open the scroll and its seven seals.’

(Revelation 5,5)

And here once again the association with Christ, the mystic lamb, is evident.

LION DESTROYER

In the Bible there are references to destructive and violent lions. For example, in chapter 7 of the book of Daniel the prophet has a vision in which four animals appear, symbolising the four great monarchies destined to be destroyed before the coming of the Messiah. The first of these is ‘a lion with the wings of an eagle’.

The terrible horses of the sixth trumpet of the Apocalypse of John have heads that resemble those of lions and a third of humanity is exterminated by the fire, smoke and sulphur that come out of their mouths.

Even the psalms often refer to destructive lions

For example, in psalm 17 the wicked are described as follows:

‘They are like a lion

seeking to devour its prey

or like a young lion lurking

in secret places’

(Psalm 17,12)

Whereas in Psalm 10, speaking of the wicked:

‘He lurks in ambush like a lion in his den.’

(Psalm 10:9)

And we could go on with many other examples.

THE KEEPER OF THE SACRED PLACE

The lion is often depicted as the guardian of the sacred place. We often see it at the entrance of churches, particularly Romanesque ones. His task is not so much to prevent and discourage entry, as to warn the profane not to venture without awareness into the place that is the revelation and home of the divine, with the risk of attracting the wrath of the being that lives there. In short, it is a presence that warns man that he is at a breaking point, a discontinuity between the profane and the sacred.

In short, he plays the role of ‘guardian of the threshold’ and in this capacity he is often depicted in the prothyra and architraves of Romanesque churches as we have already seen, for example, in the case of the Collegiate Church of San Quirico d’Orcia

Sometimes we see a pair of identical lions depicted around the sacred tree, a symbol of elevation and resurrection. Or depictions with the same meaning.

Here, for example, on a lintel of the church of Beaulieu-sur-Dordogne, in France, we see two lions side by side around the tree of life.

In this other depiction, and here we are in the tympanum of the church of Saint-Gabriel, also in France, on the left is the story of Daniel in the lion’s den and, next to it, Adam and Eve. This is not a random juxtaposition because, in this case, Daniel, thrown by his enemies to the beasts as food, represents Christ’s victory over death. Jesus, the new Adam, restores eternal life to humanity.

The lions that populate Romanesque portals often have a terrible appearance, like guardians, because the sacred is always terrible and must be approached with fear. In this respect it is similar to the snake or dragon that in many cultures guard the sacred tree.

As the presence of the tree of life reminds us, man cannot follow his path towards eternal salvation except through death. And this is another aspect of the symbolism of the lion at the threshold of the sacred place. And it is also the reason, as we have seen, for the association between tree and lion. Man can only follow the path of the tree of life pointing towards the sky by passing through the death of the body. And here we move into the symbolism of the man-eating lion.

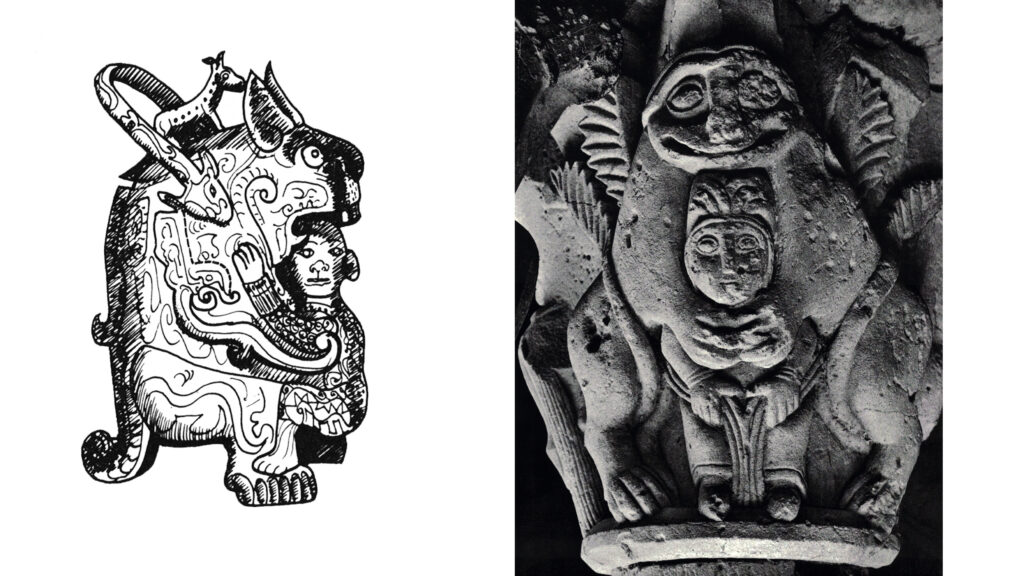

In Chinese art we sometimes find monsters, like the one in the image on the left, with small beings in their mouths that almost seem to be curled up like defenceless children in their mother’s womb. The absence of the lower jaw clearly indicates that there is no crushing.

Romanesque art uses other solutions. Sometimes we see the monster, often the lion, in the act of swallowing the person it is holding tight to it, but apparently without hurting them. Sometimes we see it simply holding the person tight, almost as if in a protective gesture.

Although in this case it would be more appropriate to think of the protection that the faithful find inside the church against the forces of evil. We see this clearly in this image, on the right, of two lions with a single head embracing a man, depicted on a capital of San Benet de Bages, in Spain.

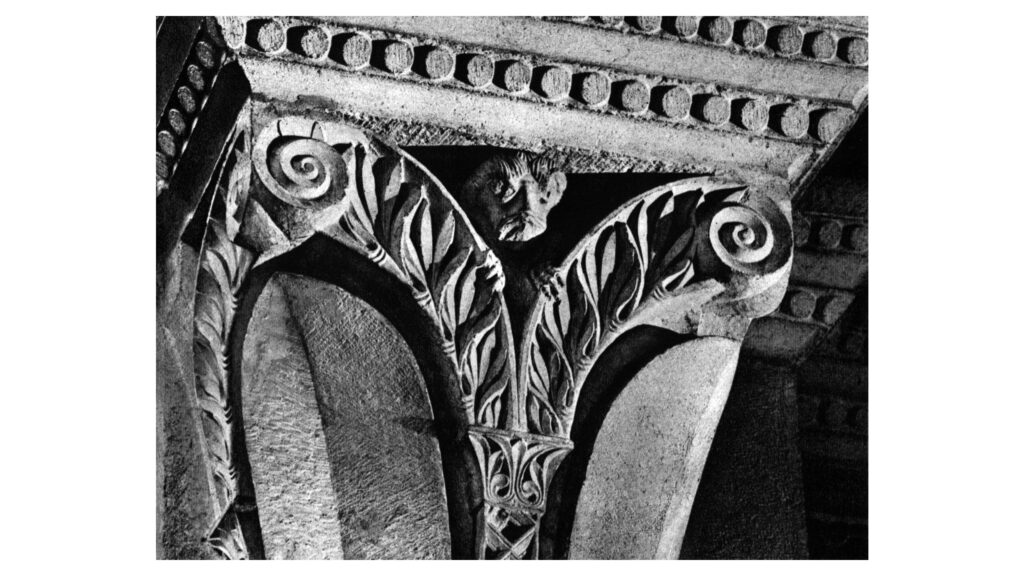

The act of swallowing implies the concept of regeneration. And often the man being devoured is depicted with a face that radiates serenity. Here we see some examples. In these depictions, the practically constant presence of plant elements refers to the tree of life.

The man-eating lion is very similar to other creatures that swallow and then reject their prey, such as Jonah’s whale. Here are two examples.

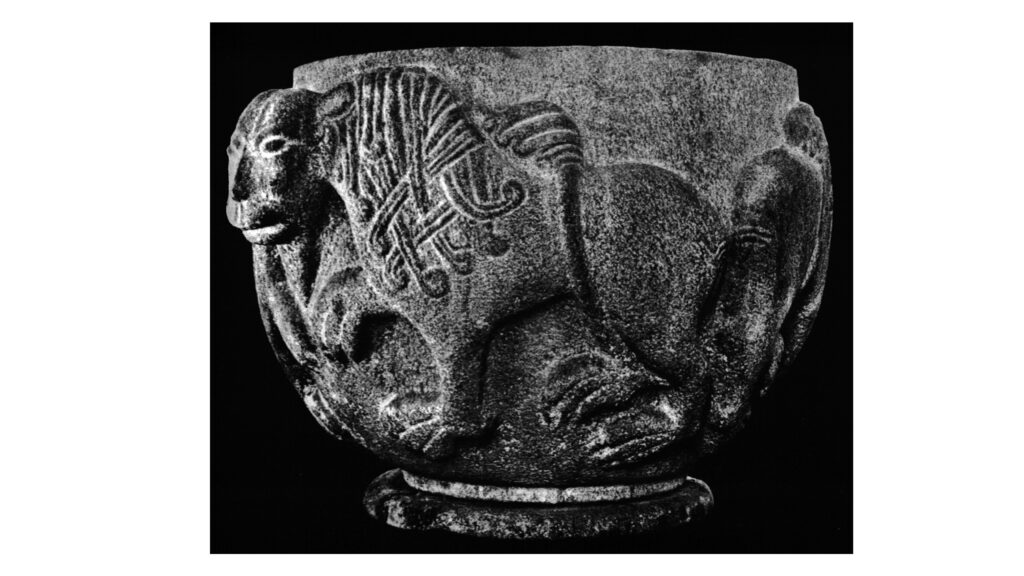

The last thing to note is that the association between lions and resurrection explains their presence, sometimes, on baptismal fonts. In the image, you can see a beautiful example of a baptismal font decorated with a lion that is found in Denmark.