Fantastic beings: sirens. The story of a transformation, between seduction and death.

The being that is half human and half fish is a very common type of depiction in other areas too, but in Europe no other monstrous being can boast such a complex transformation, both physically and symbolically.

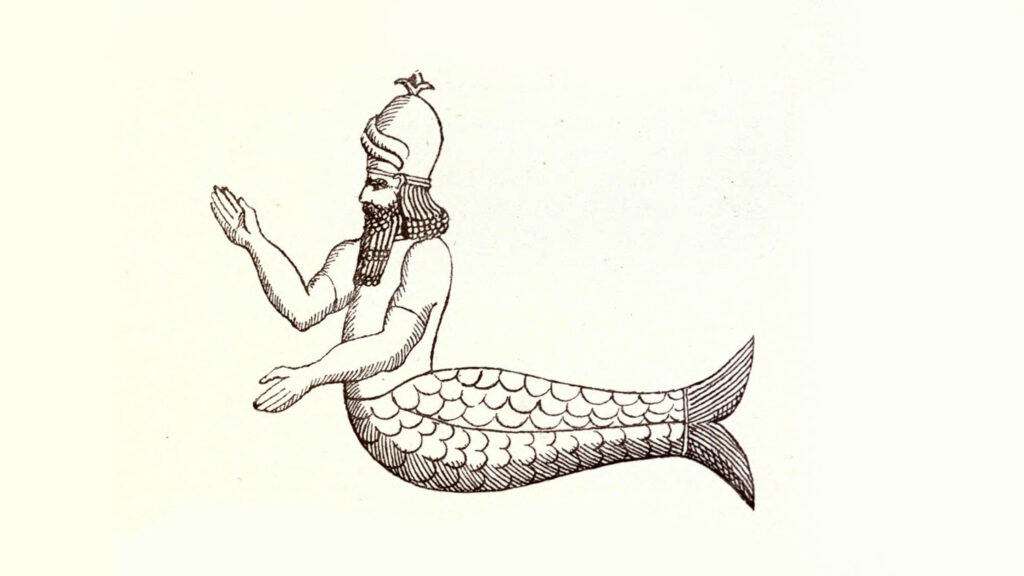

Even if the first depictions of half-man, half-fish beings date back to the Babylonian world, as is the case of the god Oannes whose natural environment was water, we can say that mermaids originated in the Greek world, but the traditions concerning them are very confused and discordant with each other. Even the name seirenes has no certain etymology and can be associated with seirà (chain, noose) or the verb seirazein (to tie with a rope), both possible references to the role of the sirens as enchantresses.

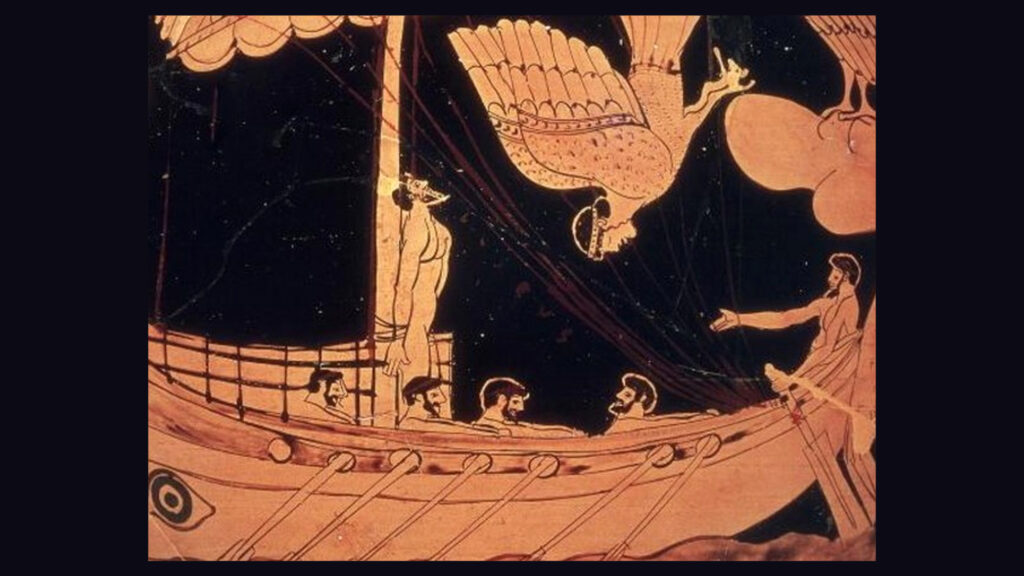

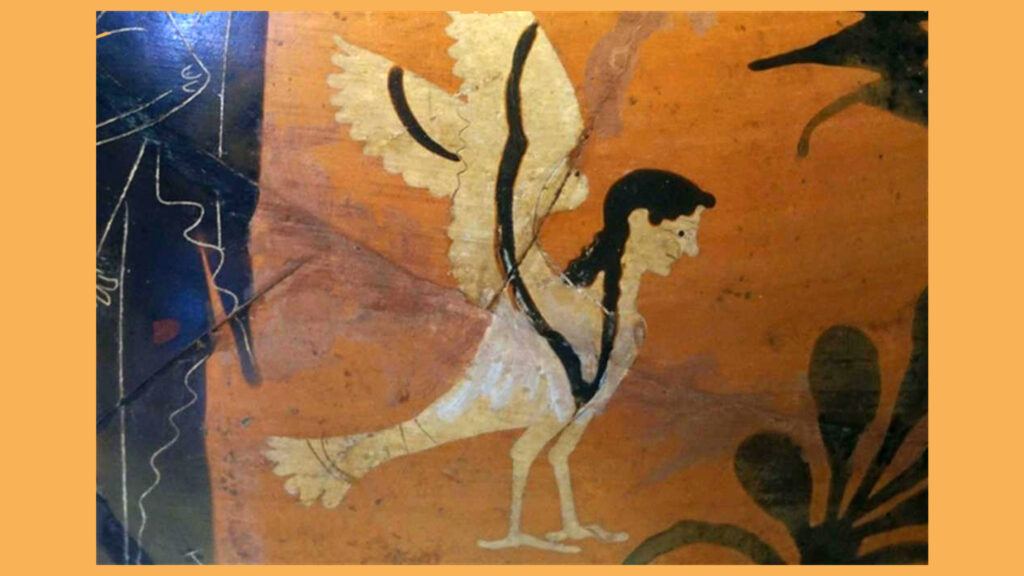

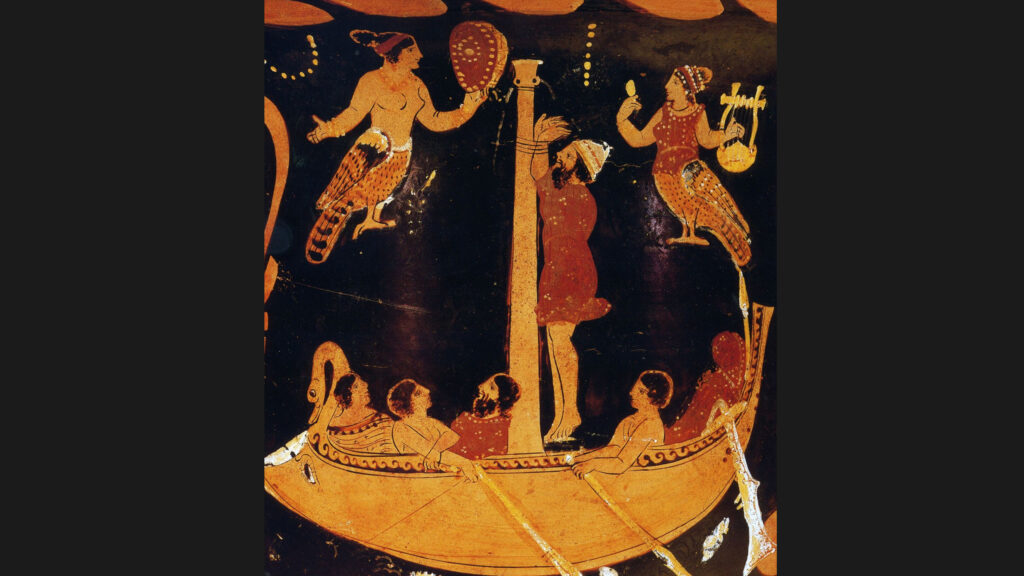

Homer does not physically describe the sirens. Ulysses, to resist their seduction of which he had been warned by the sorceress Circe, has himself tied to the mast of the ship and his companions have their ears plugged. A deadly seduction that is not based on sex but on a song that promises unlimited knowledge. There is a relationship between sirens, knowledge and death that is common to many ancient myths. In the numerous subsequent paintings and sculptures, they are depicted with the body of a bird and the head of a woman.

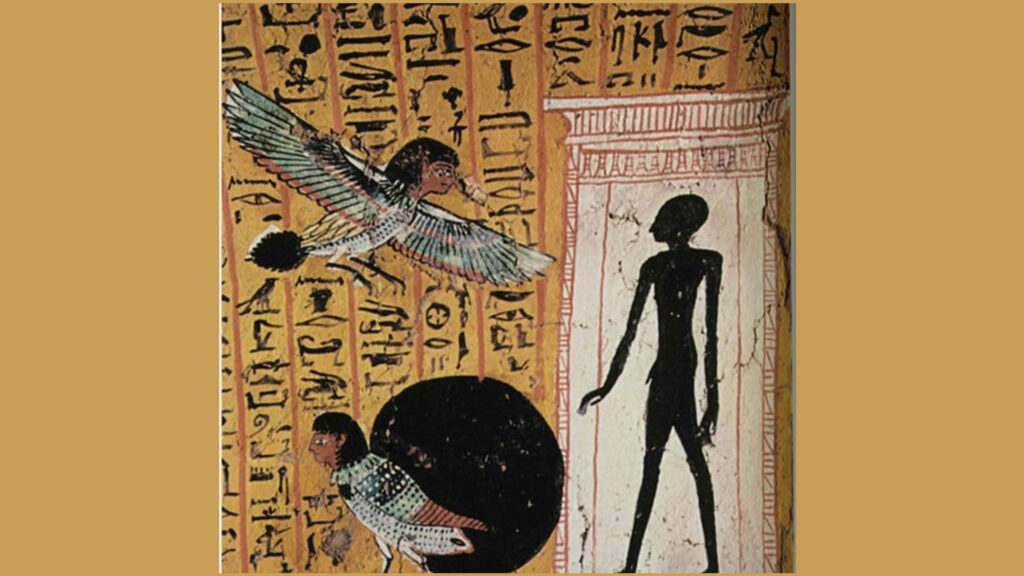

This shape probably derives from Egyptian depictions of the Ba’, the bird-soul of the deceased. Although, despite the similarities, the siren will never be assimilated to the soul.

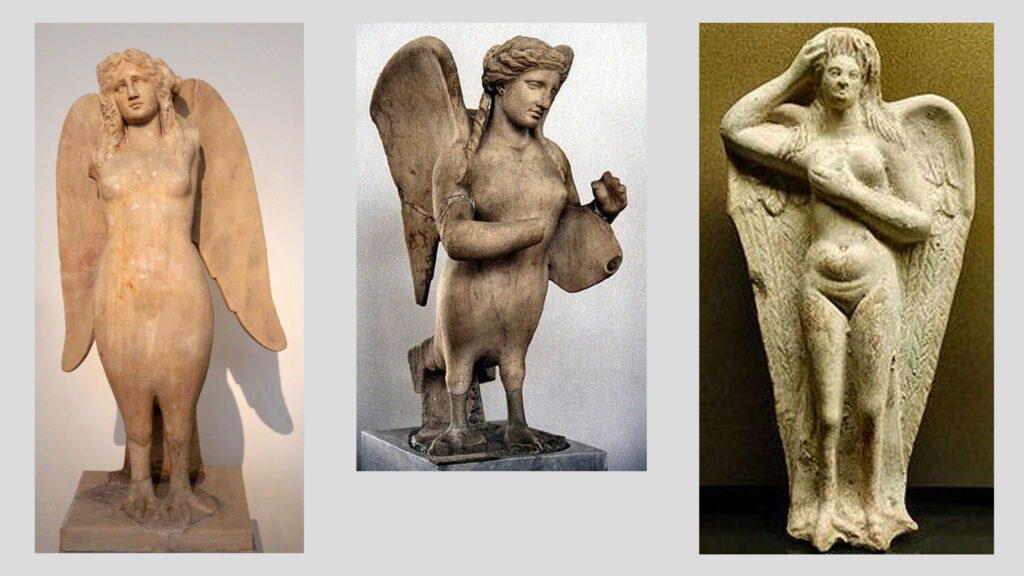

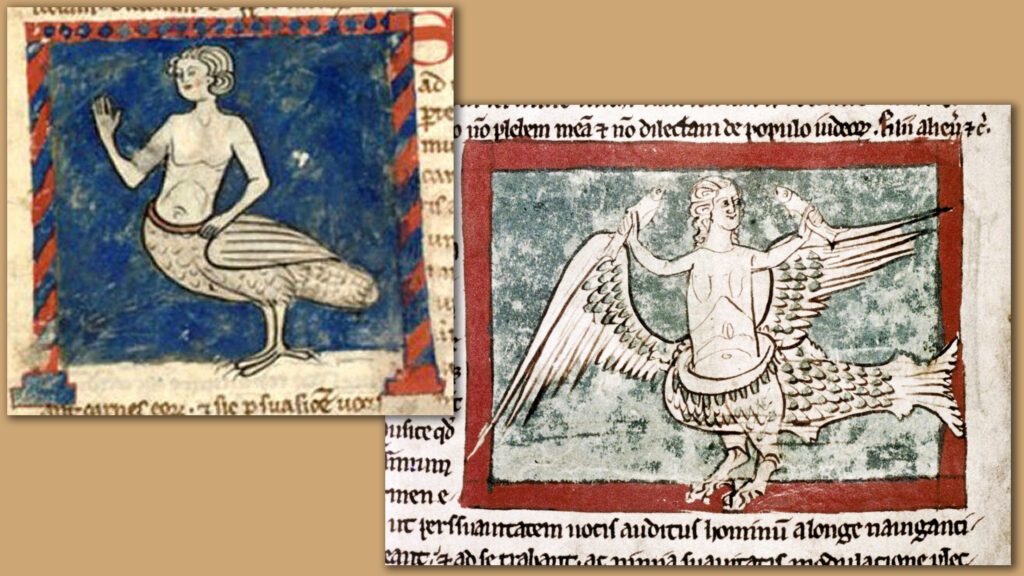

Over time this representation tends to become more humanised. Arms appear, then breasts, then the whole torso. Only the lower part and the legs remain in the shape of a bird. Sometimes these creatures are even depicted with an egg-shaped lower part.

In ancient times mermaids were devoid of any physical attraction. Poetry extolled the power of their song, while figurative art celebrated their peculiar appearance.

Since ancient times sirens have maintained a certain ambiguity and are associated with death. As we have seen, death is already present in the Odyssey. And in fact the sirens’ seduction appears fatal to men. Eros and Thanatos. And their voice, sweet and bewitching, is an instrument of death:

‘Whoever rashly grasps the shores

Of the Sirens, and hears their song, will

Neither his faithful wife nor his dear children

Will come to meet him on the threshold in celebration.’

(Odyssey XII, 55-58)

Because of their link with death and the soul of the deceased, bird-women often appear in funerary contexts, especially in the Eastern, Egyptian and Greco-Roman traditions. The scene of Ulysses and the sirens is often depicted on Roman sarcophagi from the 3rd-4th century AD. And it will still have a certain popularity until the medieval and renaissance periods.

But there’s more. The figure of the mermaid recalls the Babylonian Lilith, goddess of death, depicted as a naked woman with bird’s wings and feet. If this is true, we can easily include mermaids among the other demons of death.

However, starting from the 7th century BC, they acquired a peculiarity that distinguished them from other winged demons. This process of differentiation was favoured by the association of sirens with the funerary cult. This was a popular cult as opposed to the Olympic one, in which the sirens became a kind of useful and apotropaic divinity that it was necessary to propitiate.

In the Hellenistic period, funerary images of sirens multiplied, often in terracotta, and sometimes a large number were placed on the burial site.

This beneficial and compassionate attitude of the sirens towards the dead is associated with a well-attested function in art and literature, namely that of psychopomp, of guides of souls to the afterlife. This is why sometimes the funerary sirens carry in their arms a soul represented in the form of a small human figure.

However, in the Greco-Roman sphere we see an evolution that could be defined as steeped in misogyny and anti-feminism. Little by little the figure of the siren is detached from metaphysical evil, from death, and instead represents moral evil. At a certain point, there is an increase in the number of depictions that emphasise their physical charm and coquettishness, with an emphasis on their clothing and jewellery. An example of this type of representation comes from Magna Graecia and dates back to the 4th century BC.

With time, the erotic aspect of the sirens’ seduction, completely absent in Homer, became more accentuated, as did their coquetry until, starting from the 1st century AD, sirens were increasingly presented as a symbol of vice and sensual pleasure.

Christianity adopted this misogynistic attitude. The Fathers of the Church had no hesitation in using the term ‘siren’ to indicate animals, monsters or evil spirits that lived in deserted places and near the sea. This was probably because popular tradition had long associated them with Lilith and demons, who were feared as nightmares due to their alleged vampirism.

Even the story of Ulysses was christianised and ended up being represented on sarcophagi. The mast of the ship to which the Greek hero is tied becomes the cross of Christ (antenna crucis) to which the Christian must attach himself to overcome the crossing in the midst of temptations.

‘Pass your ship beyond this song, creator of death; it is enough that you only want it and here you are, victor over perdition; attached to the wood, you will be freed from all corruption, the Logos of God will be your pilot and the Holy Spirit will make you approach the heavenly ports”

(Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus 12,118)

This image will be developed in the preaching and commentary of the following centuries with an increasingly transparent juxtaposition between sirens, lust and the female figure from whose songs the Christian and especially the religious must keep at a safe distance.

In the same vein, sirens will also come to symbolise the seduction of heresy.

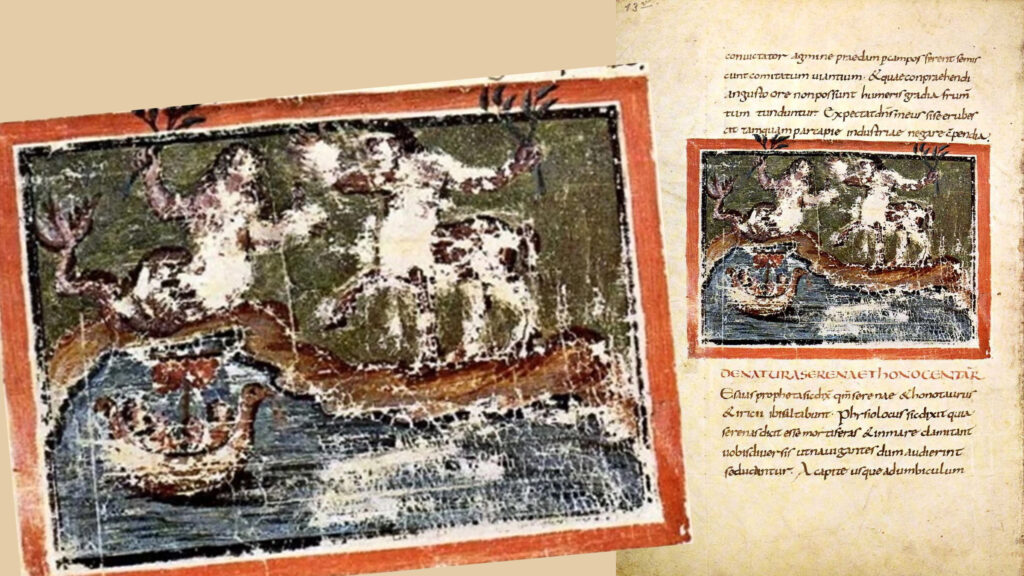

Let’s follow the evolution of this figure. For Physiologus (a text written between the 2nd and 3rd century AD in Alexandria, Egypt) the siren is a being that is half human and half goose. For Isidore of Seville (7th century) she is also partly bird. Later, however, she loses her wings and acquires the scaly tail of a fish.

This transformation is recorded for the first time in the Liber monstrorum from the 7th-8th century:

‘The sirens are sea maidens who deceive sailors with their beautiful appearance and tempt them with their song; and from head to navel they have the body of a virgin and are in all respects similar to the human species; but they have scaly fish tails which they always hide in the whirlpools’ (I, VI).

It is not clear why and how this change occurred, in which the author of the Liber monstrorum played an important role even if, it must be reiterated, for some time to come we find the mermaid with the body of a bird in bestiaries and other depictions. And there are even cases of contamination between the two types of sirens that can have, for example, the wings and feet of a bird but also the tail of a fish.

It should be noted that during the period in which the Liber monstrorum was written, mermaids were gradually confused with Germanic and Celtic water deities.

However, in 9th century texts we still find a disconcerting inconsistency between the text and the related illustrations. For example, in a Carolingian manuscript, the Physiologus of Bern (circa 830) we find the description of a bird-mermaid accompanied by a miniature representing a fish-mermaid. This, however, testifies to the persistence of different traditions.

As we have already said, depictions of creatures that are half woman and half fish can already be found in Assyrian-Babylonian art. From there they migrated to the Greco-Roman tradition, where they were linked to aquatic divinities known as tritons, but without any connection to the name of the siren. Evidence of mermaid-fish from this period is, however, extremely rare.

What is certain is that the mermaid with a fish tail, single or double, would at a certain point gain the upper hand and remain so definitively.

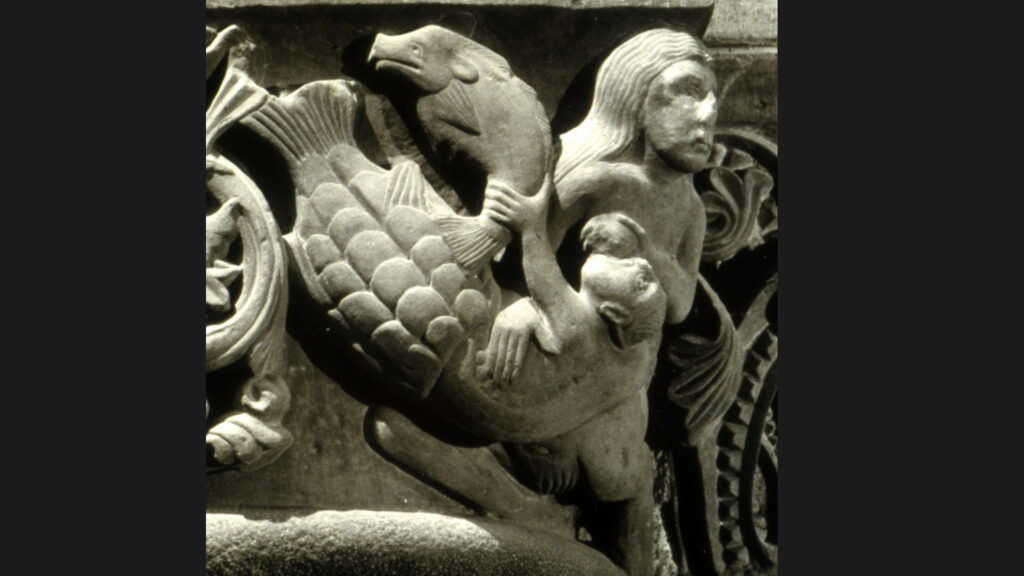

However, even in the 11th and 12th centuries, artists and writers did not definitively opt for this type, so much so that we see the two types of mermaid-bird and mermaid-fish coexisting. We even find both in the same composition, as can be seen in a capital of the cloister of the cathedral of Elne, in the south of France.

It must be said that during the course of this evolution, and in the wake of the writings of the Fathers of the Church, the sirens lost their more ancient connotations and were gradually reduced to a profane sexual symbol. In short, they were the inspiration for vice and, consequently, Satan’s tool for inducing men to sin. It is therefore not surprising to see them depicted as diabolical beings and symbols of the infernal world. It is therefore not surprising to find them represented together with other monsters, as in the church of Termeno (Tramin), in South Tyrol.

The relationship between sirens and the devil is emphasised by the sirens’ typically demonic attributes such as horns, or serpentine tails as can be seen in a 12th century capital in Montoñedo (Galicia).

We must also not forget that the being with two natures (human and animal) is the personification of the sinner, in particular the lustful, who becomes, as St Bernard says, ‘almost a beast’ and the male equivalent of the siren is the centaur who is often depicted alongside the siren.

The siren now embodies the frivolous and seductive woman and is often depicted dressed in fashionable clothes and, perhaps, with her hands in her thick hair, a sign of lust. As can be seen in a 12th century capital from central France.

Sometimes we find her depicted as if she were looking at herself in a mirror, comb in hand. The stereotype of female vanity.

Or let’s observe the sensuality that emanates from this mermaid that is sculpted on the grandiose portal of the abbey church of Vézelay.

Borgogna, Francia, chiesa abbaziale, portale, sec. XII

In short, in medieval times the siren became the emblematic figure of woman. There is certainly a misogynistic component but we must also note that the criticism of women in this period is part of the theme of De contempu mundi, the contempt of the world and the affirmation of vanity and the rapid passing of earthly things.

Given the essentially negative context of the figure of the siren, a symbol of the femme fatale and in some ways demonic, it is surprising to find the siren depicted as a loving mother intent on breastfeeding, as we see in a capital from Basel (around 1200).

We are therefore faced with a positive context, like the case of the mermaids who saved people from shipwrecks, as attested in texts starting from the 11th century and which we also find depicted on capitals, as in the case of the church of Notre-Dame de Cunault, in France.

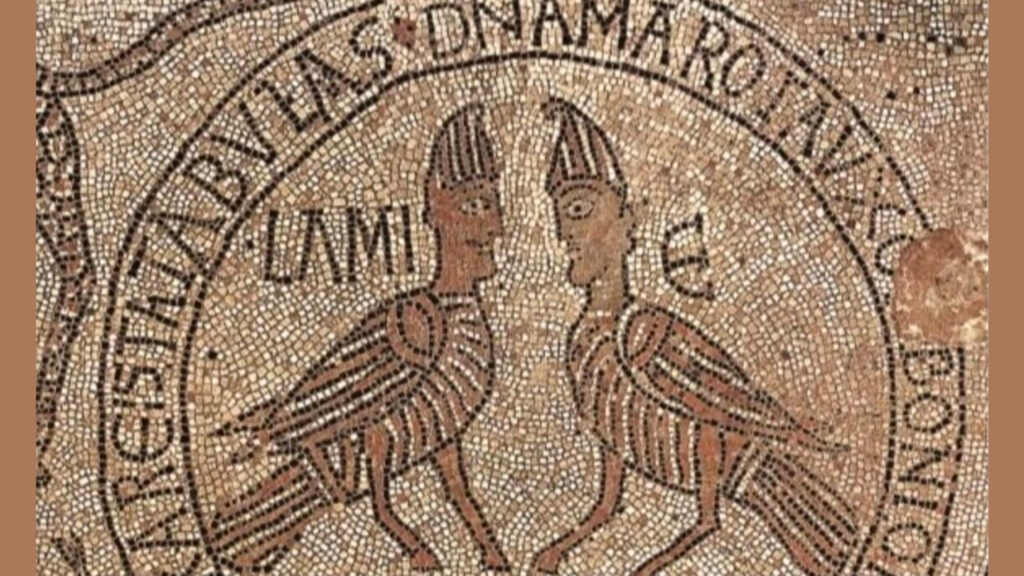

But above all, we must also note the persistence of a popular tradition that comes from far away and that sees mermaids as beings similar to vampires and almost similar to the lamiae of antiquity, terrible vampire-like creatures that devour men. This tradition can be found, for example, in the mosaics of the cathedral of Pesaro that depict two bird-mermaids accompanied by the inscription, which leaves no room for doubt: ‘Lamie’ (‘blood-sucking demons’).