The elephant in the Middle Ages: strength and moderation

The elephant is one of the animals that particularly struck the medieval imagination. This is certainly due to the many legends and historical tales that mention it. Think of those of Pyrrhus or the even more famous ones of Hannibal. Or the ivory trade and, last but not least, the discovery of fossils that, rightly or wrongly, were identified with these pachyderms. It was enough, as happened in Tuscany, for example, that mammoth fossils were found for that place to be associated with the route of Hannibal and the Carthaginian army.

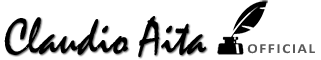

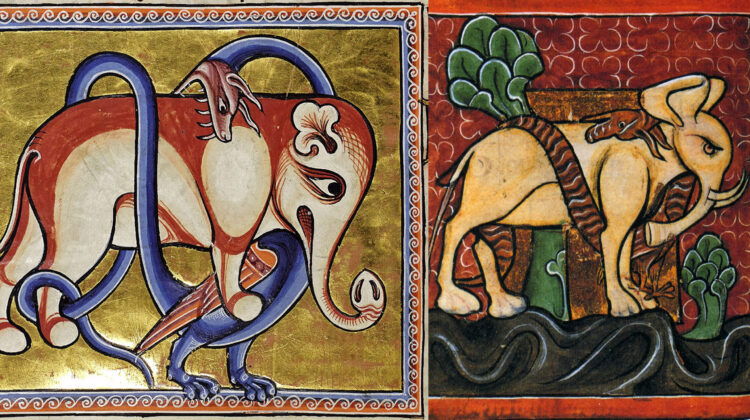

The Liber Monstrorum, from the 9th century, for example, refers to classical and patristic texts, such as Orosius or the Epistola Alexandri, or rather the letter that it was believed Alexander the Great had sent to Aristotle and in which the leader recounted his adventures in India. In the latter, Alexander said he had seen white, black, red and even multicoloured elephants. This would explain the very particular colours of the elephants we see in medieval miniatures.

Obviously, medieval sculptors couldn’t have models to hand. The texts mention the one given to Charlemagne by the Caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, in 797. The elephant’s name was Aboul Abas and, having arrived in Italy, he then crossed the Alps to arouse the curiosity of the Germans for a long time. Then, in 1255, Henry III received another as a gift, this time in England.

Despite this scarcity of live models, the elephants depicted by Romanesque artists are unexpectedly realistic, unlike other exotic animals. The fact is that the sculptors or illuminators could rely on the depictions on fabrics that came from the Orient and on the elephants represented in the chess game in that piece that would later become the bishop (with an interesting semantic shift, given that the original Arabic term al-fil that indicated it, actually means ‘elephant’). Obviously, if the features were fairly accurate, the same cannot be said for the colouring, which did not emerge from the reliefs or the chess pieces.

The interesting thing is that such an exotic animal, which the men of the time would have had difficulty in seeing directly, is also represented with surprising frequency on medieval capitals. In France alone, there are at least twenty examples in Romanesque sculpture, not to mention the countless miniatures that depict it.

We can mention the capital with two elephants facing each other from the abbey church of Saint-Jean-de-Montierneuf in Poitiers, now in the Museum of Sainte-Croix, or the one with the same subject from the church of Perrecy-les-Forges. In the latter case, the cosmic tree touching the sky is depicted between them.

However, what determines the success of the elephant in medieval art is certainly its exoticism, to the point of making it a symbol of imaginary places. It is not for nothing that we often find it depicted together with other animals far from the common experience of medieval man.

In Souvigny it is represented together with a griffin, a mermaid and a unicorn, as well as imaginary animals and people. In Perrecy-les-Forges the elephants are placed next to the siren and the fauns. In Charité-sur-Loire, the elephant is next to a dromedary, a dragon, a griffin and the Agnus Dei.

In Aulnay, above the elephants there is the inscription ‘HI SUNT ELEPHANTES’ as if they were a particularly significant element from particularly distant lands. It is significant that in this church, the capital representing them is located in the nave that opens with a portal representing all sorts of monsters and that ends with the apse depicting the damned of the Last Judgement. However, as we shall see, this is not intended as a condemnation of this animal.

As in the case of Perrecy-les-Forges, the elephant is often found in high places and associated with luxuriant vegetation, as if to make it an inhabitant of the Earthly Paradise, just like Adam and Eve but, unlike them, free from original sin.

Such a bizarre and exotic animal could only spark the imagination of medieval commentators. It was credited with the gift of always knowing which direction to take, with wisdom, temperance and moderation. And because of its size, it was obviously taken as a symbol of impregnable strength, with the structure it carried on its back to accommodate the king or queen.

But one characteristic that was willingly attributed to them was chastity. It was thought that, due to their temperament, they didn’t mate until after ingesting the root of the mandrake plant. Ultimately, elephants only engaged in sexual intercourse for the purpose of procreation. Precisely because of this alleged characteristic, St Peter Damian (1007-1072) cited elephants as an example for laymen because ‘when urged to perform the reproductive act, they turn their heads elsewhere, thus showing that they are acting under the compulsion of nature, against their will, and feeling shame and disgust for what they are doing’.

It must be said that the Bible itself mentions this. More precisely, in the first book of Maccabees, it tells of King Antiochus’ 32 elephants, each equipped with a wooden tower tied with a strap to the animal and on which 4 armed men could stand. Medieval commentators also wanted to compare this image with the image of the woman in the Song of Songs (4, 4) whose neck is compared to the tower of David: ‘Your neck is like the tower of David, built as a fortress; a thousand shields hang from it, all shields of warriors’.

According to Richard of Saint-Laurent, an important theologian who died around 1250, these two passages allude to the Church and, consequently, to the Virgin, but they can also be applied to the elephant, a symbol of chastity and strength and, as happened in chess and in the story of the Maccabees, surrounded by soldiers on foot.

The elephant also symbolises baptism, because it was believed that the female elephant gave birth in the waters of a pond while the male stood guard to scare away the dragon. Being the winner over the serpent, just like the ‘woman clothed with the sun’ of the Apocalypse, according to Richard of Saint-Laurent, is one more reason to compare it to the Virgin.

This is why the two fantastic animals, the elephant and the dragon, fighting each other, are often represented in medieval miniatures.

Here are two beautiful examples, the first from the Aberdeen Bestiary (12th century). The other from the manuscript MS Bodley 764 kept in Oxford (second half of the 13th century)