Does Christian hell derive from that of ancient Egypt?

In the Christian imagination, hell is seen as a place of torment, an underground world of eternal fire, of punishment for the wicked and so on. But why is it so similar to the hell as depicted by the ancient Egyptians? Many medieval frescoes, with their depictions of torments and demons, could very well have been copied on the wall of some tomb in the Nile valley from a few thousand years ago without arousing any surprise. In fact, even the ancient Egyptians imagined a hell that could easily hold its own against any horror film. The question is: why this similarity? Is there really a relationship between the two concepts of the afterlife, in two civilisations that are apparently so distant?

In fact, there is an explanation, as we shall see.

Let’s start by describing what this hell was like, the place the ancient Egyptians were so afraid of. And who went there.

It should be emphasised that, unlike other ancient cultures, the Egyptian Underworld had a variety of aspects and a much more varied geography than those of their neighbours, who limited themselves to painting the afterlife as a grey and sad place.

The Egyptians were concerned about their afterlife. For them, their tomb and their funeral had to be managed according to very specific rites so that the afterlife would mean a new existence and not eternal destruction. It was therefore necessary to arrive at death well equipped and instructed on what to do in order to face a path made up of dangers, traps and hostile entities. In short, the problem was not to make it a moment of destruction but, on the contrary, of regeneration and transition to a new existence.

An indispensable condition was the preservation of the body, the material support of the spiritual entities Ba and Ka, the real meaning of which escapes us. This led to the development of embalming techniques, often, however, reserved for pharaohs and subsequently for the upper classes. The mummified body also had to be equipped with everything necessary for a normal existence, from furnishings to food and clothing, and in abundance. What’s more, to give an impression of even greater abundance, these were also engraved on the walls.

It was also important that the tomb not be damaged because this would create big problems for those in the afterlife who would then take revenge on the person responsible for the damage.

The Egyptians believed in the power of words, which could be fundamental in overcoming obstacles. Therefore the means considered most suitable for overcoming the pitfalls on the path to the afterlife were magic formulas that had to serve both to defend oneself from evil entities and to demonstrate knowledge of the infernal characters and places. If the dead person proved that he did not have this knowledge, he was doomed to destruction.

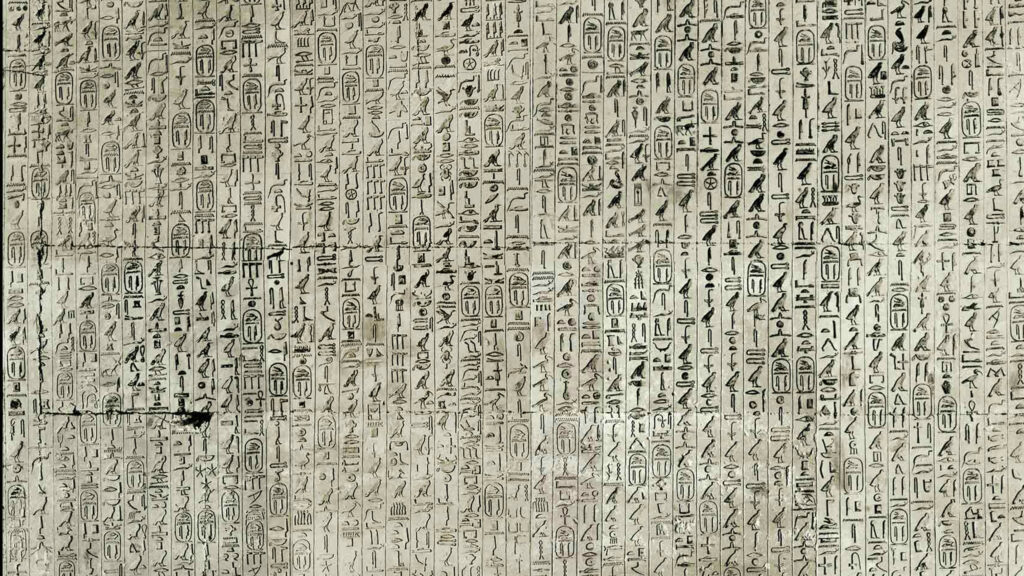

Texts of formulas intended to help the deceased face the dangers of the Underworld have been collected in texts of a certain consistency. The oldest are the so-called ‘Pyramid Texts’ which were written around 2300 BC and were intended for the exclusive benefit of the pharaohs.

In these texts, the concept of judgement to be faced after death appears for the first time, as well as some formulas for being reunited with one’s family in the afterlife. Very interesting is the presence in some sarcophagi of a text, ‘The Book of the Two Ways’, accompanied by a real map of the afterlife with its traps and terrible guardians.

The following period (approximately 2150-2000 B.C.) was a time of crisis for the power of the sovereign and many feudal lords acquired greater independence. During this period the Pyramid Texts were expanded with additional sacred writings to form other corpora of funerary literature that we find inscribed on the sarcophagi of private citizens and which are in fact called ‘Sarcophagus Texts’.

These texts develop the role of Osiris and the judgement that the deceased will have to pass.

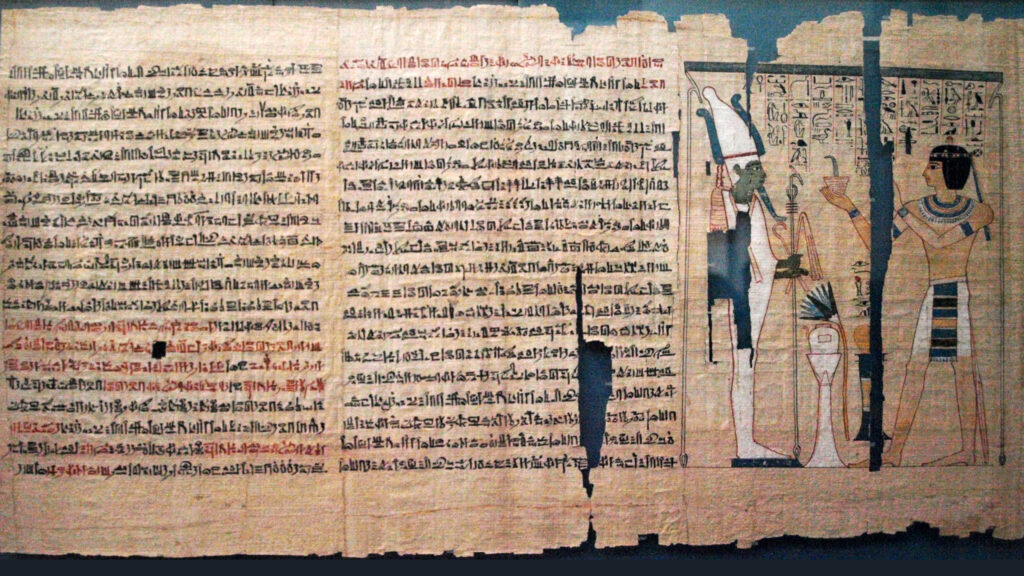

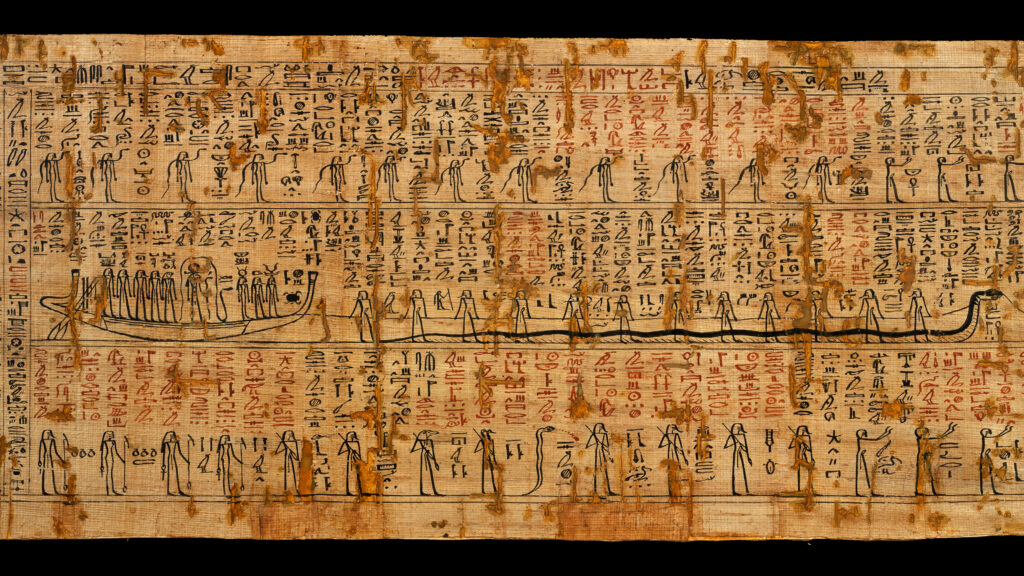

Around the 16th century BC it was the turn of the famous Book of the Dead, also known as ‘The formulas for leaving by day’, which replaced the Sarcophagus Texts. 190 chapters of this text have been identified, but they are not all found in a single manuscript. Only a part was regularly transcribed on the papyrus scrolls that were to accompany the deceased to his dwelling place in the underworld. In any case, most of the formulas derive from the Texts of the Sarcophagi.

In the Book of the Dead the realm of the dead is definitively placed in the underworld, of which Osiris is king and Ra, lord of the sun and daily life, merely visits every night on board his solar boat. Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead speaks of the terrible judgement of the soul before the court, called the ‘Hall of the Two Truths’ before 42 judges presided over by Osiris. Chapter 125 includes two ‘declarations of innocence’, one addressed to Osiris and one to the 42 judges who had rather unsettling names such as ‘Devourer of Shadows’, ‘Breaker of Bones’ and so on.

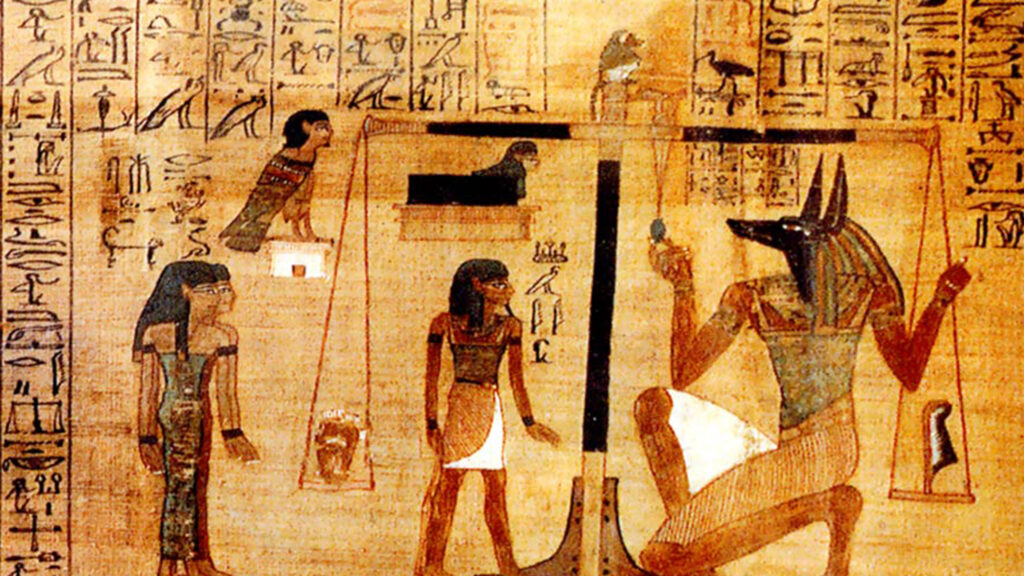

Chapter 30 of the Book of the Dead, on the other hand, concerned the behaviour that the heart of the deceased should have at the moment of judgement. The heart had to be weighed on the ‘scales of justice’ while on the other pan was the Maat, the absolute rule of life, which the deceased, in life, should have followed, symbolised by a feather. The incantations were intended to silence the heart, which more than any other part of the body could testify against the deceased, revealing his sins. Chapter 30 was engraved on a large hard stone scarab that was placed in the mummy where the heart would have been, and was supposed to prevent the deceased from showing hostility towards or expressing judgements against the deceased. And for this reason it was called the ‘scarab of the heart’.

Now, if the deceased did not pass the judgement of the ‘Hall of Two Truths’ or ‘of the Two Maat’, what punishment would he face?

For one thing, the punishment par excellence, the most cruel, was annihilation, which was equivalent to a return to primordial chaos. This penalty was carried out by having the deceased devoured by evil demons or by fire. This concept is already present in the Pyramid Texts.

Another curious fear for an Egyptian was that in the afterlife he might find himself ‘falling upside down’, i.e. with his head at the bottom and his feet at the top. In this position the physiological processes would be reversed and the poor deceased would find himself with his mouth and throat full of his own excrement and urine. Some magic formulas are specifically designed to avoid such a situation.

The Pyramid Texts also referred to other fears such as being locked up in prison, being separated from one’s family, being bitten by snakes or other animals, being forced to spend eternity in darkness.

The same concerns are expressed in the later Texts of the Sarcophagi. Here too, there is a great fear of annihilation caused by horrible demons, merciless devourers. And there is also the fear of fire, which completely destroys the body, which is the fundamental support for the existence of spiritual entities. In the Book of the Two Ways, which is included in it, there is mention of a lake of fire that the dead must avoid and of the fire through which the deceased must pass on his way in and out of the world of the living.

In fact, it should be noted that in the Book of Sarcophagi, the references to the term ‘fire’ evoke the idea of a fiery hell where the dead constantly risk succumbing. And of a hell where physical torments are also inflicted. There are references to mutilations that also lead to ‘definitive’ death, such as decapitation or the cutting off of limbs. In some passages, the deceased is invited to ‘keep his head and not die the death’ (formula 677) or ‘save his neck from him who could cut it off’ (formula 94). Despite the difficulty of reading the texts, it seems that these executioners are demons with the heads of monstrous animals.

During the New Kingdom period, starting from the 16th century BC the Books of the Afterlife appeared. These were no longer collections of formulas to help the deceased overcome the dangers of the afterlife, but real guides to the Underworld, where the places of the afterlife were described in detail and, of course, the terrifying places and torments that awaited the deceased who had not been absolved in the ‘Hall of the Two Truths’ were also illustrated. These texts were called ‘Books of the Amduat’ or ‘Books of what lies in the afterlife’.

The torments inflicted on the damned were of various kinds. One category involved the body of the deceased, which could be deprived of its burial, and even those who had been properly embalmed could see their corpses uncovered, the bandages torn off by evil divinities who carried out the sentence ordered by the court of the afterlife.

Other punishments included a lack of light and total immersion in darkness, and they were also unable to hear the voice of the Sun god who every night called the chosen ones to a new life. The damned were also deprived of speech and were forced to dwell in the ‘place of silence’ for all eternity.

In short, the damned had to suffer every kind of deprivation and be cast back into the depths of darkness. The perverse ‘sat on their heads’ and ‘ate their own faeces and urine’. They were surrounded by pestilential odours and were terrorised by the roars of their tormentors. Other punishments included having their limbs tied together, being chained to poles and tortured by demons with unsettling names such as ‘Compressor’, ‘Terrible’ and ‘Binder’. They were also imprisoned in wooden cages and mutilated and burned with swords and knives or sharp flames.

The place of these torments was called a ‘slaughterhouse’. A terrible place ruled over by Sekhmet, the lioness goddess of war, carnage and epidemics. She was assisted by cruel demons who, in addition to torturing people, lived off the blood and hearts of their victims.

But fire played a fundamental role in the hell of the Egyptians. It could come from the eyes of demons, from the eye of the sun-god, from the mouths of serpents, from animated swords and so on. The damned were tormented by fiery winds, by a sea of fire that smelled pestilential at a certain time of the night, while at another time fire filled deep pits that were guarded by demons and snakes and in which bodies, souls and shadows were continually consumed while the god Horus screamed at them, according to the Amduat (189):

‘Your bodies must be tortured with the Knife that torments, your souls annihilated, your shadows trampled, your heads cut off! Do not stand upright, but lay your heads down! Do not get up again, but lie down in your graves! You cannot escape, you cannot escape!’

To this were added the cauldrons in which the heads, hearts, bodies, souls and shadows of sinners were thrown to be cooked. What’s more, they were placed upside down to make the pain even more acute. Snakes and demons stoked the fire. In short, there was no hope or mercy for the enemies of Osiris.

But in the Egyptian hell they didn’t just attack the bodies of sinners. Remember that what we could define as the ‘soul’ for the Egyptians was composed of a similar entity that was indicated by the term ba and the shadow, called sheut or shuyt. Therefore the punishments could also be directed at these components of the human person. In fact, even the souls could be chained, burnt, killed, torn to pieces. And even the shadows could be torn to pieces, beheaded and so on. Both could also be thrown into cauldrons together with whole bodies, heads, hearts, limbs; they could be deprived of sunlight. In short, they could suffer the same torments to which the corresponding bodies were subjected.

The infernal punishments culminated in the most terrible of tortures, that of total and definitive annihilation. This task was carried out by a terrifying creature, Ammit, also known as the ‘Devourer’ of the dead, who appears in the funerary papyri of the New Kingdom. She was depicted with the head of a crocodile, the front part and the mane of a lion and the back part of a hippopotamus and was the direct descendant of the demons of the Book of the Sarcophagi known as ‘Swallowers’. Its enormous and very strong jaws crushed the deceased in all their components, material and spiritual, thus annihilating them and casting them into the realm of the non-existent. The place where this frightening creature operated was called the ‘Place of Annihilation’ and was the deepest place in hell. There, chained, the guilty were guarded by huge snakes with fiery breaths while they waited their turn.

The Egyptian hell was a terrible one. Which is very similar to the traditional Christian concept of hell, as we mentioned. So much so that the hell described by Dante himself is very similar, not to mention the many other works on the subject, the frescoes and so on. It’s hard not to think of a connection given that all the other ancient cultures, including the Romans, have a completely different concept of the Underworld. But what is it?

Many people forget that Egypt in the first centuries AD was one of the places where Christianity was formed. And it was the birthplace of monasticism, especially the desert around Thebes, the Thebaid. Just think of people like Antony abbot, Pachomius, Macarius, Paul and so on. And many others who followed them.

They were highly motivated characters who had decided to go and live in the desert as hermits, to escape a world in the grip of sin and decadence. But they always had a large following and a considerable influence on civil life. However, we must not fall victim to the cliché of the meek and shy monk. These characters and, above all, their followers, were often fanatics, ‘Taliban’, as we might call them today, who lashed out physically against any evidence of the pagan past. But they didn’t hesitate to terrorise good Christians with images of the afterlife that were so familiar to them, and that they could draw directly from inside the violated tombs where they themselves had sometimes established their hermit dwellings. With the aim of making them good Christians, of course, according to their mentality.

In various texts they talk about guardians of the afterlife, dangerous paths to follow, flaming pits from which an unbearable stench emerges, and so on. All images that very often seem to be taken from the funerary texts of the ancient Egyptians.

In a text, the Martyrdom of Macarius of Antioch, there is a description that is too similar to what an ancient Egyptian would have done. The devils have the heads of ferocious animals (lions, crocodiles, bears, dragons) exactly like the demons depicted in Egyptian books. And the soul of sin, after a passage through fire, finds itself in the Hall of Judgement, where Jesus has taken the place of Osiris as supreme judge. After this it is handed over to the ‘Eater’ by the crocodile head (which resembles the Egyptian ‘Devourer’) who, with the help of worms and snakes, tears the sinners to pieces ‘without them dying’.

This is perhaps an extreme case, but many other testimonies point in the same direction.

It is clear that our image of hell derives from the ancient Egyptian concept of a place of torment for sinners, which was obviously later reworked by the Coptic monastic environment.

Which will introduce some innovations compared to the sacred Egyptian texts, above all for a clearer correlation between guilt and punishment, something that was not so clear in the previous tradition where all the guilty were considered guilty and assimilated to the ‘enemies’ of Osiris, to those who caused his death without any particular distinctions. More generally, they were attackers of Maat, universal order and harmony, of which Osiris was one of the pillars. They were, in practice, by their own choice, part of the Chaos that surrounded the orderly creation and continually threatened to destroy it. For the ancient Egyptians, therefore, the existence of sinners, of evil men, constituted a danger that could not be tolerated and they had to be driven back into the abyss, into Chaos itself, to end up once again in Nothingness, to which, by their choice, they belonged.

Something similar would later be included in the texts of the first Christian writers for whom the devil and evil represented nothingness, the absence of good, and those who chose this path were destined for eternal damnation to be suffered in hell, among the torments inflicted by the devils.

The maximum punishment for the Egyptians, which was to be kept away from the sun and light, also recalls the punishment of being far from God and deprived of his vision that characterises those condemned to hell, but also to limbo, according to Christian theologians.