The boundaries of chaos. The limits of God’s power.

One God, infinite God, omnipotent God… This is what we have always been taught. A principle that, in fact, is a dogma of faith. So everything is fine and dandy?

In reality it’s not so simple, especially when the Bible itself sets limits to the kingdom of God, whose power, if we look closely, is not really so universal. Here and there, in the sacred text, references emerge to the fact that there are parts of the cosmos over which not only does God have no jurisdiction, but which apparently do not even belong to him. In short, the Kingdom of God has very precise limits, boundaries that separate it from another world, another entity. That of the Enemy, of death, of chaos.

On closer inspection, the entire history of the cosmos, from its creation to its end, is resolved in the confrontation between these two opposing polarities, order and chaos, God and anti-God, and in their precarious equilibrium.

First of all, a premise. With all due respect to those who still insist on supporting the historical validity of the Bible and continue undaunted with phrases like ‘The Bible was right’ and so on, the reality is decidedly different.

Especially after what has emerged in recent decades and continues to emerge from the exegesis of the biblical text, from archaeological excavations, from studies of comparative linguistics and especially since we began to study the history of the people of Israel not only as an appendix to the Bible but by correctly inserting it in the more general Semitic and Phoenician context.

The Bible cannot be cited among the direct sources for the historical reconstruction of Israel because, first of all, even if it also uses more ancient testimonies, it is a collection of relatively recent texts. Most likely from the Hellenistic period, but we must not forget that the Hebrew text of reference, the Masoretic text, is just over a thousand years old. The Bible is in any case a much-manipulated text and was compiled with a particular and conscious perspective that no longer had anything to do with ancient Judaism. What we have today is a text that is the result of countless reinterpretations and amendments. If not a real rewriting.

Given the vastness of the subject, it is not possible to go into more detail here. What we can say for sure is that the Bible is absolutely not consistent with the events and the mentality it claims to describe.

The history of Israel itself, from Abraham to the Exodus, for example, could very well be a forgery and an artificial reconstruction created by a priestly caste for their own theological and other purposes. It is a reconstruction and consistent with the image that this caste wanted to portray of itself and the narrative it wanted to impose. A caste that reinterprets its own roots and conceals many details and practices that we know to be common instead in the ancient Near East and also in the Palestinian area.

Not that older elements don’t emerge, mind you, but the biblical text is so tampered with that it is sometimes not easy, if not impossible, to understand the original message. Just as it is difficult to reconstruct the theological thought and mentality of the most ancient Jews. And to know exactly how, in a more archaic phase, the Jews conceived their God, or even their gods.

And yet these elements are there. And mythical elements, dating back to a remote time, are found in fair quantity even in a text, such as the Bible, that tries to present itself as historical. And we don’t only find them in the first chapters of Genesis, as one might expect, but also for example in the prophetic texts, in the psalms, in the book of Job, which testifies to the great survivability of these mythical narratives.

It must be said that the Jews of ancient times, like their neighbours, did not conceive of death as an inexplicable and abstract fate, but as an individually characterised enemy. And the Canaanite Semites, and therefore the Phoenician populations, of ancient Ugarit and so on, depicted it as a deity called Mot.

Mot, death, is an enemy that lives in a specific place, sheol, the underworld, the inferno. We often hear that the Jews conceived of the afterlife as a place of non-existence or of suffering due to separation from Yhwh. But in this case, we are simply projecting a much later mentality onto ancient documents. The reality was certainly very different.

Furthermore, if the dead cannot harm, this would not explain God’s hostile attitude towards the dead, as would emerge from some passages where God even intervenes violently against the deceased. Which seems disconcerting, given their presumed inability to harm.

‘The dead will not live; the realm of the dead will not rise again. You have punished them and destroyed them, caused them to forget forever’ (Isaiah 26:14)

‘The realm of the dead trembles beneath the waters; the waters and the inhabitants of the realm of the dead shudder; the nether world is laid bare before him; there is no shelter for Abaddon’ (Job 26:5)

From this and other passages, we can deduce that sheol, the world of the dead, is in a certain sense something independent from God and extraneous to his creation. It is the realm of chaos and death that lies at the margins of the world created by God and that, indeed, constitutes a constant threat to the orderly creation. From this point of view, God’s fight against Mot, death, can be seen as the fight between the forces of chaos and the ordering power of God that made the ‘creation’ of the world possible. With this act, God limited the power of chaos, he limited it to the confines of creation, but he didn’t succeed in annihilating it.

To die, according to the Bible, means to be torn from our ordered world and enter a different world, a chaotic world outside the jurisdiction and power of Yhwh.

At any moment the powers of chaos could prevail once again, cancelling the power of creation and requiring a new battle between God and the Enemy. In short, it is a perpetual battle that determines the very existence of the world and to which no one is a stranger. As the book of Wisdom (1, 12-14) says:

‘Do not provoke death with the errors of your life, do not bring ruin upon yourselves with the works of your hands, because God did not create death and does not enjoy the ruin of the living. He in fact created everything for existence; the creatures of the world are healthy, in them there is no poison of death, nor do the underworlds reign on earth.’

The question that arises is: if God is not responsible, then who created death? It is obvious that, as was the case in all the other cultures of the ancient Near East, for the people of Israel too some other entity in competition with God came into play. And what we are talking about, and will talk about in more detail shortly, is a clear trace of a very ancient mythology from when Judaism embraced polytheism, and that subsequent interventions have not managed to completely erase.

Returning to the world of the dead, this was very important in Hebrew cosmology, as it was in Mesopotamian and Egyptian cosmology. To put it simply, we can say that the world of the dead is the counterpart of the world of the living and the two realms are not so much in competition as in a state of equilibrium that can be broken when the inhabitants of one world decide to invade the other. Yhwh has no jurisdiction over the realm of the dead.

The realm of the dead is governed by other divinities that at a certain point are identified with a single figure, the Enemy. That Enemy who has always been fighting with Yhwh and who tries to take pieces of his territory from him by invading it with chaos. It’s all clear from the very first lines of Genesis where God wanders over the initial chaos, which is described with the words tōhû wa-bōhû, which is normally translated as ‘[the earth was] formless and empty’, but which could very well have been the names of two divinities opposed to God.

Over time, the Jewish tradition has tried to mitigate this dualism by introducing the figure of Satan, who is still a creature of God. But the dualism has never completely disappeared and, we repeat, it must have been the reality of an earlier phase of Jewish theological reflection.

The interesting thing is that the dead become the citizens of this world opposed to God (who is, as the Bible says) the ‘god of the living’, or rather they end up in this realm that represents chaos in all its destructive aspects and that opposes the creation of the world and the order of God. Indeed, we could even say that it, like tōhû wa-bōhû, pre-exists or is contemporary with God himself.

In short, the realm of death continually tries to expand and surrounds the realm of Yhwh on all sides. The most problematic points for God, obviously, are the boundaries between the two realms, which are in particular, as we shall see later, the sea and the desert.

The most ancient myths do not speak of a creation from nothing. The first act of creation is to set a boundary, to effect a separation. The uncreated chaos must be limited, contained within precise boundaries. This act of division, of separation, is found in almost all creation myths. Sometimes we see a real struggle between the creator god and the primordial chaos.

Many passages in the Bible are absolutely clear on this point:

Take for example Job 38, 8-11:

‘Who shut up the sea behind doors, when it brake forth, as it were, out of his mother’s womb? […] And I set my bow in the cloud, and saw it in the cloud: and I made it an everlasting ordinance, and it shall be a sign and a wonder for ever.’

The same concept can be read in Psalm 104, 5-9:

‘You laid the foundations of the earth, so that it will not totter. It was covered by the deep as with a garment, and water stood above the mountains. At your rebuke they fled; at the voice of your thunder they trembled. They went up into the mountains, and down into the valleys, to the place which you had assigned for them. You have set a boundary and they shall not cross it, they shall not again cover the earth’.

From these passages it is clear that the sea and its waters are perceived as hostile and personal entities, whose “pride” is contained by God within the limits necessary for the survival of the cosmos.

The same is evident in the story of the creation in Genesis, where the state of widespread and indistinct chaos is described, ‘the earth was tōhû wa-bōhû’, ‘formless and empty’. And the act of creation takes place through separation: that of light from darkness, of upper waters from lower waters. Finally, God orders the waters to gather in one place so that the dry land appears.

We can also quote Psalm 74, 13-17:

“You divided the sea with your power, you crushed the heads of the tanninim upon the waters. You broke the heads of Leviathan, you gave him to the people, to the ṣiyyîm, to be eaten. You opened up springs and streams, you dried up everlasting rivers. The day is yours and the night is yours, you have fixed the moon and the sun. You have set all the boundaries of the earth, and you have marked out summer and winter.

The boundaries of the earth are here understood in a very concrete sense to indicate the concrete barriers that hold back the forces of chaos.

In the book of Proverbs (8,24-29) we read the traditional story in which Wisdom tells of how she was at Yhwh’s side since the creation of the world:

“I was given birth as long ago as the beginning of the deep, before the waters were gathered together, before the mountains were settled, before the hills, […] When he created the heavens I was there, when he drew a circle on the surface of the tehom [the abyss]; when he fixed limits for the sea and commanded that the waters should not pass his command; when he established the foundations of the earth.

This passage can be associated with another passage from the book of Jeremiah (5,22):

‘Do you not fear me, O Lord? Will you not tremble at my presence, who have placed the sand of the sea as a boundary, by a perpetual decree, so that it cannot pass it? Though its waves toss, they cannot prevail; though they roar, they cannot pass through.’

In short, Yhwh creates the world by setting a boundary to limit the power of chaos. This concept is expressed very clearly in the book of Job (26, 10):

‘I have drawn a circle on the waters, up to the boundary between light and darkness’.

This image, of God with a pair of compasses in his hand, is found in many medieval miniatures. While God is interpreted as the ‘architect of the cosmos’. In reality, as we have seen, the meaning is quite different

Another image in the Bible that describes creation as limiting the power of chaos is that of Yhwh sealing the entrance to the abyss. Later Judaic tradition linked this to the ‘foundation stone’ upon which God supposedly built the world. And this is probably what is alluded to by the ‘cornerstone’ that God placed at the moment of creation.

We find this concept, for example, in the book of Job (38,4 and 38,6):

‘Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? […] Where are its bases fixed or who laid its cornerstone?’

The Talmud and Jewish tradition identify with this ‘foundation stone’ the rock on which the Temple of Jerusalem is built and which represents the tangible sign of God’s victory at the time of creation and the submission of the Enemy that still persists. It is worth remembering that the rock of the Temple still has an underground cavity under the Dome of the Rock, well known as the ‘well of souls’.

We also recall that the concept of the foundation stone that also serves to contain the forces of evil is also found in the controversial passage in which Jesus ‘invests’ Peter:

‘You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it’ (Matthew 16:18).

In both respects, as we have seen, the Gospel passage is much more ‘Jewish’ than it may appear at first glance. And not for nothing, Matthew is the evangelist who more than any other wanted to present Jesus’ preaching as a consequence and fulfilment of the prophecies of the Old Testament.

Another concept with which the Bible expresses the boundary between order (the kingdom of God) and chaos (the kingdom of the Enemy) is that of doors. In the Bible, mention is made of the gates through which the sea is held back (Job 38,8), but also of the gates of death (Job 38,17; Psalm 9,14 and Psalm 107,18), the bolts of the ‘earth’ in the sense of ‘underworld’ (Jonah 2,7). All these seem to be equivalent expressions to indicate the bronze portals closed by iron bars that hold back the forces of chaos (cf. Psalm 107:16).

An echo of this can be found in ancient myths and in later literature, in particular in the Syriac version of the Novel of Alexander, in which it is said that the Macedonian king, having reached the northern limits of the world, built a great bronze door with two bolts. This door was then to be destroyed after 940 years, by divine anger due to the sins of men.

This is the Novel of Alexander. According to some scholars who refer to an obscure passage of Isaiah (27:1), the guardian of this door would be Leviathan, the demonic serpent that represents chaos and that, blocking the gates of hell, prevents the deceased from escaping from Sheol. God’s final act, at the end of time, as can also be seen in the Book of Revelation, will be to kill the Dragon, the Leviathan, to definitively penetrate the kingdom of the Enemy.

It must be said that, if the passage from Isaiah is doubtful, subsequent Jewish tradition would seem to confirm the role of Leviathan as guardian of the boundaries. In the book of Enoch (60,13), a fundamental text for the definition of the Christian concept of devil, it is said that God, or a spirit delegated by him, keeps Leviathan under control. Every now and then the monster manages to loosen its grip and tides form. This encroachment, even if momentary, of the waters of chaos bears witness to the position of Leviathan, which would be right on that boundary desired by God and which holds back the waters.

That in any case the Leviathan, the sea monster, is on the edge that should hold it back, is also indirectly inferred from the Apocalypse, which seems to implicitly affirm that its place is on the edge of the Abyss.

“Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven with the key to the Abyss and a great chain in his hand. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years; he threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations until the thousand years were ended. (Rev 20,1-3)

After what we have said so far and what emerges from the Bible itself, we can reach two conclusions:

1) The forces hostile to God already existed before creation and therefore are equivalent to Yhwh because, just like him, they are uncreated and eternal.

2) The cosmogonic struggle, that is, the struggle over the origins of the cosmos, does not allow God to completely eliminate the power of the forces of chaos, but limits himself to keeping it within certain boundaries.

In short, God’s power is not absolute but has limits. And these limits are determined by the ongoing conflict between Yhwh and his adversary. The limits separate the kingdom of God from the kingdom of the Enemy, over which God has no power.

The evolution of Israel’s religious thought has been a journey from Semitic-type polytheism, to which Yhwh also belonged, to an increasingly accentuated monotheism. Yet, as we can see, this evolution has not succeeded in eliminating the presence of chaos, or rather death and evil. If this is not dualism, we are certainly not far from it. The presence of evil is an unsolvable problem and one that is difficult to reconcile with the idea of a single God.

We have already seen how the Talmud and Jewish tradition identify the rock on which the Temple of Jerusalem is built as God’s ‘foundation stone’, a ‘foundation stone’ that serves to keep the forces of hell and chaos in their place. The Temple, therefore, represents the tangible sign of God’s victory at the time of creation and the subjugation of the still persistent Enemy. We should remember that the rock of the Temple still has an underground cavity under the Dome of the Rock, well known as the ‘well of souls’.

The Temple also represents the centre, the navel of the world. It is not for nothing that biblical tradition first and then Jewish tradition tend to identify Mount Zion with many fundamental events in the history of Israel. For example, identifying the place where the Temple was built with Mount Moriah, the place of the sacrifice of Isaac.

For example, in the second book of Chronicles 3,1 we read:

‘Then Solomon began to build the temple of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord appeared to his father David on the site prepared by David on the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite’.

This is what we could call a transference phenomenon, given that this sentence we have just read projects two other sacred places onto the temple of Jerusalem: the place where Abraham sacrificed his son Isaac, and the place where David would have erected an altar to stop the plague sent by Yahweh (1 Chronicles 21,18-26). In later Jewish literature, the place where the Temple stands is identified with many other elements, such as the offering of the gifts of Cain and Abel, as well as the first sacrifice offered by Adam and that of Noah at the end of the flood, Jacob’s dream, etc. These are all events that would have taken place in the centre of the cosmos.

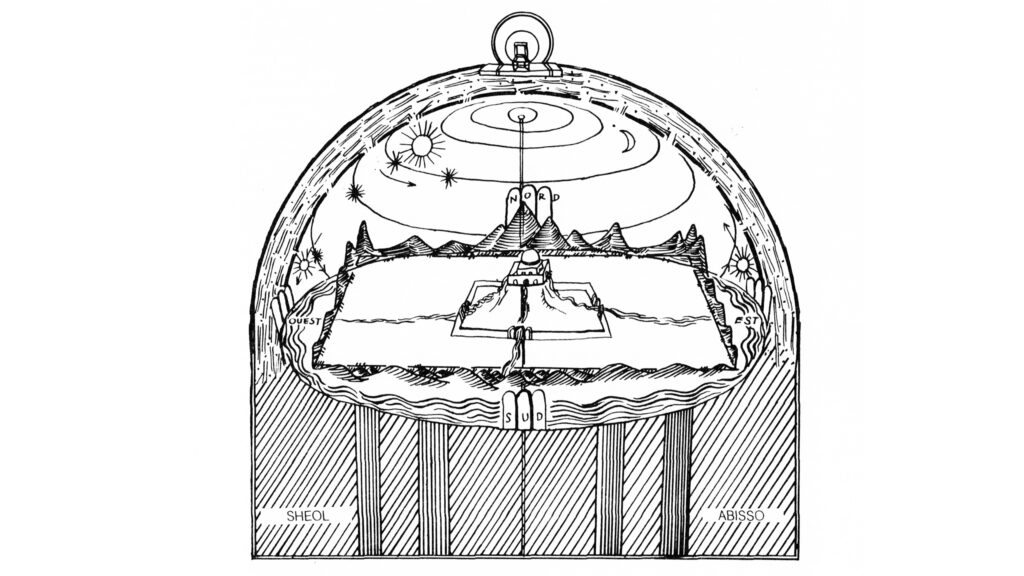

If the Temple of Jerusalem is the centre of the cosmos, it is the fulcrum of the universe as conceived by the ancient Jews. The centre in a vertical sense, first of all. According to symbolic Hebrew cosmology, the seat of God is above, the place where men reside is in the middle and the kingdom of the dead is below.

Let’s take, for example, Psalm 115 (16-17):

‘The heavens are Yhwh’s heavens; he has given the earth to all mankind. The dead do not praise Yhwh, nor do those who go down to the dûmā’

Apart from the problem of the last term, dûmā, which is normally translated as ‘silence’ but which perhaps would be better translated as ‘fortress’ in the sense of ‘citadel of the afterlife’, it is interesting to note that the psalm itself reiterates that the dead ‘do not praise’ God, therefore, they do not recognise his authority

This area, as we have already seen in the first part of the video, therefore does not belong to God, but is the realm of the Enemy.

This division is emphasised in another passage, this time in Exodus (20,4):

‘You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth below or in the waters below the earth.”

This passage is significant for two reasons.

1. The prohibition to build images of what is in the various parts of the universe seems to express, albeit in a veiled manner, the prohibition to worship the divinities that inhabit it.

2. The reference to water underground again emphasises the identification between chaos, or the realm of the dead and the Enemy, and water, as we have already seen with the sea that is barely held back by Yhwh and relegated to the outside of creation.

It will be Paul, in his letter to the Philippians (2,10) who will affirm that only with Christ will the submission of the three realms be total.

‘[…] so that at the name of Jesus every knee of the heavenly, earthly and infernal beings shall bow’.

But with Paul, obviously, we are in a very different context.

The three zones of the universe are connected by a vertical axis that passes through the Temple Mount which, as we have seen, represents the centre of the universe. In the figure, a schematic representation of the cosmos as conceived by the ancient Hebrews. It is a great architecture of which traces can still be found in Romanesque architecture. A topic we have already dealt with previously.

But the centre of the universe, the navel of the world from which, in the symbolic Jewish world, is also the place where creation began. From this point, from the temple mount, this creative force radiates over creation, with the result that as one moves away from this point, God’s ordering force diminishes until reaching the realm of chaos. We move forward in concentric circles until we reach the realm of primordial chaos.

On closer inspection, the concept described above is also shared by earthly kingdoms. In ancient cultures, the king was usually God’s representative on earth. Defending one’s kingdom from enemies, droughts, floods, etc. also meant stemming destructive chaos. If these forces crossed the border, it was a sign that the king was not fulfilling his duties properly.

In a considerable number of cultures, including those of the Mediterranean and the Near East, a great deal of attention was paid to the physical efficiency of the king through various systems. When this failed, the king was simply eliminated. Those who have read James Frazer’s The Golden Bough will be well aware of how common this attitude was in practically all cultures until relatively recent times.

In these contexts, attention was also paid to the fact that the sovereign was always in a state of purity, which was considered fundamental for the maintenance of the cosmic order, or at least that of his kingdom. In the Bible itself there are many examples in which a transgression, even involuntary, by the sovereign, brought misfortune on his people.

One example is found in Genesis 20,1-8. In this episode, King Abimelek, deceived by Abraham who had introduced her as his sister, makes demands on Sarah who is in fact his wife. In this way, even if in good faith, the king had committed a mortal sin against himself and his people. And, once he had learnt the truth, he addressed Abraham:

‘What wrong have I done to you that you should expose me and my kingdom to such a sin?’ (Genesis 20,9)

All the women of the royal family had become sterile and God himself had threatened Abimelek and his family with death.

More generally, expanding to a wider context than the biblical one, a wrong attitude on the part of the king does not simply translate into a punishment inflicted by the gods on a king for a moral failing, but into situations that place, in common thinking, the king in a position of impurity and which, in short, weaken the power of the sovereign allowing the forces of chaos to enter the kingdom and disturb the order that we could define as cosmic.

Let’s say that the role of the monarch, be he pharaoh or king, was to defend and if necessary reinforce the barriers that were erected at the moment of creation and that defend the divine order from the advance of chaos.

In fact, one of the king’s tasks was to take land from the enemy, chaos, and give it back to the order of creation. One of the titles of the pharaoh, for example, was that of the one who ‘extends the borders of Egypt’. Extending the borders of the kingdom, from this point of view, is seen as the sovereign’s personal contribution to creation, renewed with every victory against enemies or hostile and savage forces of nature. Maintaining the borders was an important element of Egyptian royalty. On a boundary stone placed there by Pharaoh Sesostri III (1846-1839 BC) we read:

‘Whoever of my sons will maintain this boundary, which my Majesty has established, he is my son, born of my Majesty. Exemplary is the son who supports his father and maintains the boundary of his parent. But whoever lets it fall and does not fight for it, he is not my son and was not born of me’.

The same concepts were adopted by the rulers of the Mesopotamian area. The expeditions of the Assyrian kings, who ventured into ever more distant and unexplored lands, were seen in a mythical light, where the king continually overcame the limits imposed by nature and man. The conquest of new lands had, in short, the purpose of expanding the order, which was threatened by hostile and evil forces. Each stele placed in a symbolic place that was increasingly distant and liminal also represented the border of the cosmos against chaos.

And to emphasise this work of expansion, also from a symbolic point of view, the materials taken from the defeated enemy were brought to the temple and to the palaces that stood at the centre of the cosmos, or were even used in their construction.

Naturally, the kingdom must be equated with the cosmos and the extension of the kingdom’s borders must be equated with the continuation of the work of creation. The sovereign’s work is all-encompassing and his work embraces all of creation. For the Egyptians the pharaoh was the ‘lord of all that is embraced by the solar disc’, while the Mesopotamian sovereign was the ‘king of the four parts of the world’.

The same happened in the Jewish world. The borders of the kingdom of Israel corresponded to the jurisdiction of Yhwh, beyond which the kingdom of the other divinities began. Israel’s borders were the borders of the cosmos; beyond them was chaos, something negative, something demonic.

‘From the desert to Lebanon, from the Euphrates River to the Great Sea, all the land which you shall take for yourselves, it shall be yours’ (Deut 11,24).

It follows that to leave Palestine is to enter the realm of death. This is probably why pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem, if they were resident outside Palestine, had to undergo purification procedures.

The same thing happened in Egypt, where foreign countries were often depicted as places of condemnation and exile, a condition that was assimilated to a sort of partial death. And the African and Semitic peoples who lived there were equated to the forces of chaos.

We can also hypothesise that the condition of exile of the people of Israel, first in Egypt and then in Babylon, can also be interpreted in this way. From a symbolic point of view, let’s say, given that the historicity of these events is increasingly being questioned. In any case, the return to the Promised Land is also seen as the victory of order over chaos. And, last but not least, we cannot fail to observe that the return from both Egypt and Babylon involves crossing the sea, the Yam Suf, the biblical sea of reeds, and above all the desert. These are border zones, liminal areas, places where the dimension of chaos begins.

This is the case with the sea of Leviathan, the dragon of the Apocalypse, and the desert, the place of demons and perdition. And perhaps it is no coincidence that the Gospels place the place of Christ’s temptation right in the desert. Where, if not there, in this place of contact between opposing worlds, could Satan ever hide?