Numbers in the Middle Ages, a bridge between man and God

Numbers play a fundamental role in the Bible and, in particular, in the book of Revelation, the text that most influenced medieval art. The Fathers of the Church, especially Origen and St Augustine, dealt with it extensively, as did later commentators such as Isidore of Seville and Rabanus Maurus.

Medieval intellectuals placed great importance on a text on arithmetic and geometry that they attributed to Boethius, but which in reality was written in the 8th century. It stated that the world was governed by two principles: unity and multiplicity. Unity includes odd numbers and expresses stability.

Multiplicity is typical of even numbers and implies change. This is because the odd number is indivisible and therefore perfect and unalterable, as is the eternal order, while the even number belongs to the mutability of time and the transience of things.

Numbers were considered so important that both Boethius and St Augustine stated that a man who did not possess mathematical knowledge would never be able to achieve wisdom and perceive the unity of creation.

This mania for numbers can also be found in Romanesque art where, in order to understand the deep meaning of the decoration of a capital, for example, one sometimes has to count the number of petals of a flower, the points of the stars, the number of leaves on the palmettes and the palmettes themselves, and so on.

1

There is only one God: ‘You shall have no other gods before me’ (Exodus 20:3). Furthermore, God cannot be represented, as is written immediately afterwards. And Romanesque art complied with this prohibition, while managing to represent unity by other means.

Unity can be represented by a point that is often nothing more than the intersection of the axes of the cross, as is the case of the intersection point of the ‘X’. This is the case, for example, of the cross drawn by the Tetramorph with Christ at the centre. Remember that the Tetramorph is the representation of the four living creatures of Ezekiel and the Apocalypse that Christianity then wanted to identify with the evangelists. In this case they are identified with multiplicity and Christ, at the centre of the cross symbolises unity. And this is just one of the possible cases.

In medieval and Romanesque art in particular, we can see the transformation of duality into unity and vice versa. This is the case of the many depictions of an animal with two bodies and one head, for example, as we see in Chauvigny Saint-Pierre where a monster with these characteristics is intent on devouring a man.

Or the divided man who dances who is in the same church, with one head and two bodies.

A similar case is the Y-shaped tree that is often found depicted in Romanesque capitals. A tree with a single trunk from which two branches extend. We can see a beautiful example of this in a capital of the church of Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy. Here the branches of the Y-shaped tree symbolise the double path granted to man. One branch represents vice, the other virtue. And the figure of the lion, symbol of resurrection and salvation, peeping out from among the branches reminds us what is at stake.

2

Two is a fundamental number in Romanesque art. Just think how often we come across two animals facing each other or side by side. Pairs of lions, dragons and two-headed snakes, Y-shaped trees with two branches as we have seen, etc.

The Bible and the writings of the Fathers are full of references to pairs: body and soul, the two Testaments, Christ and the Church, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Moses and Aaron, and so on. And the Romanesque art of pairs has represented an infinite number of them. Here are a few examples: the first is from the cathedral of Jaca, in Spain; the second from the cathedral of Modena; the third from the cloister of the abbey of Saint-Denis, now in the Cluny Museum.

Often, pairs of animals or humans or monsters change their meaning depending on their position and their context. Sometimes they even express the opposite meaning. A good example is represented by two capitals of the priory of Serrabonne, in the French Pyrenees, both of which depict two lions whose bodies form a kind of heart, as can often be seen in Romanesque art. The lion is a very complex figure and can express many meanings, even conflicting ones, even symbolising Christ and the resurrection (To learn more about this subject, I invite you to read the text dedicated to the figure of the lion in medieval art). Well, in the first case, the lions facing each other express love and life.

In the second, in the middle of the two lions that also form a kind of heart, there is a human head. Which the lions seem to be devouring. The image of the man-eating lion was often used in the Middle Ages. But here its meaning is clear, and it is a symbol of death. Of death and resurrection. Here is a beautiful example that, like the previous one, comes from the priory of Serrabonne.

Sometimes the number 2 indicates ambiguity, duplicity as is the case of the sirens with two tails that are depicted just about everywhere. Or of snakes, also with two tails.

The siren is often found paired with the centaur, her male counterpart. As in this miniature.

It must be said that the symbolism of the number two presupposes an asymmetrical relationship between the two terms. And it often expresses a relationship with a higher reality that can also be glimpsed in beings with a dual nature: mermaids, centaurs, harpies, griffins. Or of moral degradation in the case of the depiction of men with bestial attributes.

Let’s add that dualism, duplicity, is inherent in being as such and should always be seen in its positive and negative meanings. This is why we find the naked man and the clothed man, the upright being and the fallen being, the virtuous man and the vicious man. Each of the two realities must be seen in relation to the other and often both are depicted together.

3 e 4

Let’s look at numbers 3 and 4 together because, according to medieval numerology, they are closely intertwined. 3 and 4 added together make 7 and multiplied together they make 12, which are two of the most important numbers in Christian and Roman symbology in particular and symbolise the union of body and soul or the universal Church.

Three is the number of the spirit and the soul, as St Augustine said. While four is the number of the body and matter. Furthermore, the number three is associated with the sky and the circle, and the number four with the earth and the square. The interaction between these numbers and between the circle and the square is the basis of all medieval architecture. It’s a very complex subject but one of great fascination.

The number 3 is the number of the Trinity, of the days Christ spent in the tomb and so on. To emphasise this reality, medieval churches normally have three portals in the façade, three naves and three apses. This is an almost universally recognised rule, if size allows, obviously. The exception, very significantly, are the areas of southern France that had for a certain period seen the triumph of the Cathars and their dualistic vision of the world, that is to say the presence of two opposing and equal entities, one good and one evil, in conflict with each other. This dualistic concept dates back to Iranian Mazdaism and has influenced many other cultures over the millennia, including the Jews.

The fact is that several churches in these areas have two portals instead of three and two naves.

We’d also like to point out that the number 3 is closely connected to the rite of baptism. In fact, baptism is performed in the name of the Trinity and in the past, when baptism was administered in a baptismal font, the person being baptised was immersed three times in homage to the three days that Christ spent in the tomb. After all, isn’t baptism dying to sin and rising again, renewed?

The number 4 also has countless symbolic meanings. It is the number of the world. There are 4 corners of the earth, 4 points of the compass. But 4 is also the number of the elements of the earth (earth, water, air and fire), the seasons, the rivers of the earthly Paradise, the humours in the human body and, consequently, its temperaments. 4 is the number of the evangelists and the characters of the Tetramorph, the cardinal virtues and we could go on and on.

4 is the number of the Heavenly Jerusalem, a perfect cube with three doors on each side, the city of the end of time that will descend on a finally renewed earth.

Romanesque art has worked a lot on the relationship and contrast between the numbers 3 and 4, between earth and sky, between body and spirit.

A good example to understand how medieval artists thought and developed this theme, with subtleties that often escape us today, are two capitals from the church of Rozier-Côtes d’Aurec, in central-southern France. Both represent a man-eating wolf, which, in an area that was still influenced by Celtic culture, replaces the more common lion.

In the capital on the left, which is in the nave of the church, we see the wolf that has thrown a man to the ground and is about to devour him.

The man tries to defend himself by pushing away or grabbing the animal… it’s not clear. The number 3 is in the wolf’s tail, which ends in a kind of trefoil shape after passing through the man’s body. The 3, therefore the sky. The tail is also pointing upwards. The message is clear and is the same as that repeated in the case of the man-eating lions. Man, after passing through the monster’s jaws, will be reborn to heavenly life. But there is another 3, less evident, that is contained in the locks of hair that descend along the wolf’s neck. If we count them, there are 9, another divine number and the number of the heavens. As a final point, we note that the animal comes from the left, or rather, from the inauspicious side.

In the second capital, the wolf still has 9 tufts but comes from the right. The number 4 is enclosed in the four leaves but the wolf, an animal of the sky, rests only on the first 3. The fourth leaf supports a human mask while the man who is immediately beyond it evokes the human condition and probably the corruption of the flesh. The 4, the imperfect earth, as opposed to celestial perfection and our destiny.

5

Five corresponds to the five books of Moses, which not by chance make up what is called the Pentateuch, to the five wounds of Christ and so on. But it is above all the number of man who has five senses, five fingers on each limb and who has 5 extremities, arms, legs and head.

In medieval miniatures, man is sometimes represented with open arms and legs apart to better express this figure. Leonardo didn’t invent anything new. If we see it from this point of view, man can be inscribed within a pentagram with his head up, that is, correctly oriented towards God. If the pentagram is upside down, the being depicted also becomes demonic or dominated by the Evil One. The inverted man, in all Romanesque art, has something completely wrong within him. He is the man who gives in to vice and passions and thus rushes towards his condemnation.

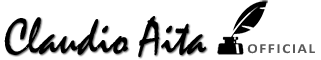

According to Hildegard of Bingen [(1098-1179)], a 12th century Benedictine mystic, a great intellectual who had a great influence in the medieval era, man is the measure of all things, as we can see in the figure on the left, taken from a manuscript of her writings, but it is also the representation of the cosmos. Here in particular he represents the microcosm, surrounded by the primordial waters, while the external figure encircles the macrocosm with her arms.

Again according to Hildegard, the number 5 is the result of adding the first odd number, 3, and the first even number, 2. ‘The even number signifies the matrix, and is therefore feminine; the odd number, vice versa, is masculine; the association of the one and the other is androgynous, just as the Divinity is androgynous. The pentagram is therefore the emblem of the microcosm’.

In short, man is governed by the number 5. But Hildegard of Bingen also makes another statement. If you look at the figure on the right, the human body is divided into 5 parts in height and 5 in width. If we consider this, the human body can be inscribed in a perfect square. It is interesting to note that this principle is very similar to that which inspired the Cistercian builders of the 12th century with the plans of their churches drawn ad quadratum, that is, by placing equal squares side by side to form a cross.

6

If 5 is the number of humanity, 6 is the number of the superhuman, of power. 6 are the days of creation and of the works of mercy.

St Augustine emphasises the unique properties of the number 6, which is obtained by adding the first three numbers (1+2+3=6), just as 10 is the sum of the first 4 numbers (1+2+3+4=10). The number 6 can be associated with the sky, being the sum of the first three numbers (3=sky), while ten, the sum of the first 4 numbers, is the number of the world (4=earth). There is therefore a relationship between 6 and 10.

But the number 6 is not only obtained by adding the first 3 numbers, but also by multiplying them together (1x2x3=6), which makes it unique.

The number 6 repeated three times, to indicate absolute but distorted power, is the number of the Beast according to the Apocalypse: 666.

7

The number 7 is not as widespread in Romanesque art as one would expect. And it has less relevance than 3 and 4, the sum of which it is.

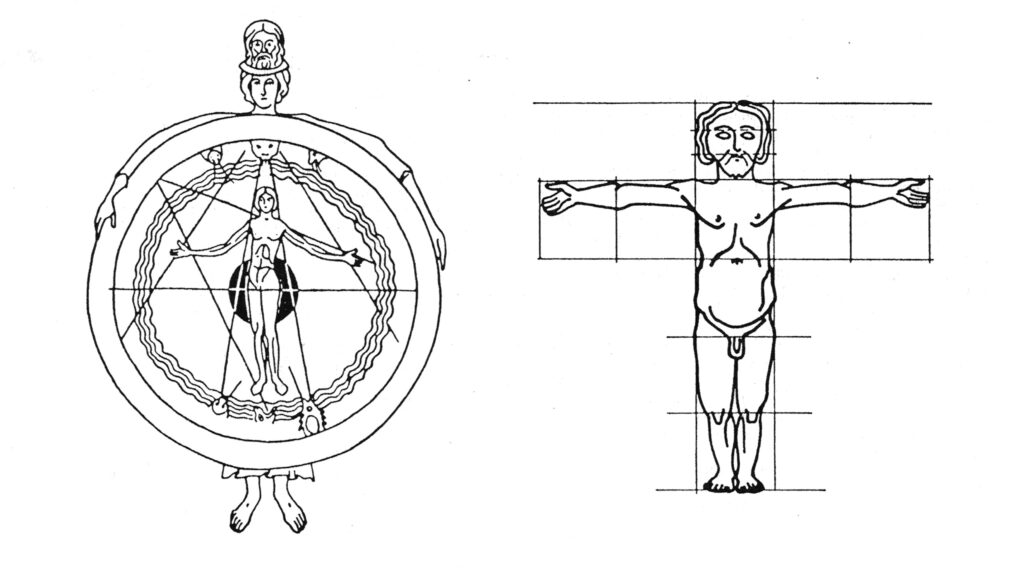

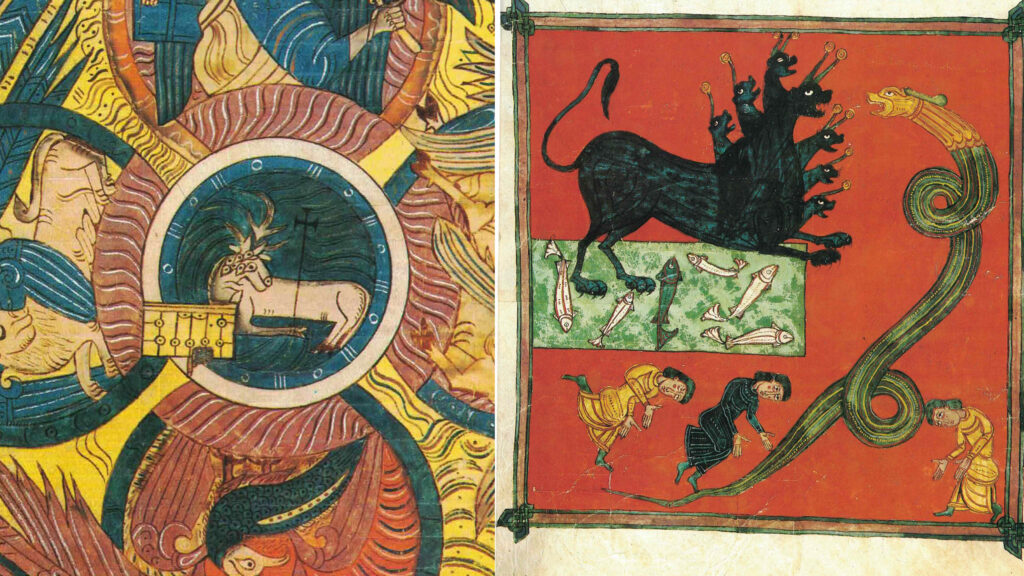

It is omnipresent, however, in the so-called Beatus, or in those richly illustrated Spanish codices that contain the commentary on the Apocalypse of Beatus of Liébana, who lived in the 8th century.

Here are some examples:

We should also note that 7 is an important number in Jewish tradition too; just think of the menorah, the 7-branched candelabrum.

But also in Christianity it represents the number of sacraments, of deadly sins, of theological virtues and so on.

However, it should be noted that if the number seven does not have the great relevance that we would expect in Romanesque art, it is also because many descriptions of the Apocalypse of John are so abstruse that it is very difficult to depict them in a sculpture or a fresco. This is not the case, as we have seen for illuminated pages, especially those of the Beatus. But there are significant exceptions.

One of these is represented by the beautiful tympanum of the church of Saint-Pierre de La Lande in Fronsac, in the French department of Gironde.

It’s worth quoting the whole passage of the first vision of John in the Book of Revelation to see how the sculptor tried to represent it.

I turned to see who it was that was speaking to me; and on turning, I saw seven golden lampstands, and in the midst of the lampstands, one that was like a son of man. He was wearing a long robe, and around his chest was a golden sash. The hair on his head was white, like white wool, like snow. His eyes were like blazing fire. His feet were like burnished bronze, when it has been refined as in a furnace. His voice was like the sound of many waters. He held in his right hand seven stars, and out of his mouth came a sharp two-edged sword. His appearance was like the sun shining at its brightest. When I saw him I fell at his feet as if dead, but he laid his right hand on me and said: ‘Do not be afraid; I am the First and the Last, the Living One; I was dead, and behold I am alive for ever and ever; and I hold the keys of death and of Hades. Write down the things you see, both those concerning the present and those that will happen afterwards. As for the meaning of the seven stars you see in my right hand and the seven golden lampstands, the seven stars symbolise the angels of the seven churches and the seven lampstands symbolise the seven churches.

Here the elements are quite evident. Saint John, with the book in his hand, is to the right of the Living One, depicted with all his attributes. We see the sword coming out of his mouth, the seven stars depicted inside a circle that clearly symbolises the sky, the seven churches on the left, also identified by a small cross. To be honest, the seven candlesticks are missing, but on the one hand they are a ‘double’ in the sense that they are the symbol of the seven churches already represented, and on the other hand a reference can be seen in the plant decoration. Here the sculptor allowed himself a little freedom even if the seven golden candlesticks are mentioned in the inscription that surrounds the tympanum: JOHES VII ECCLIIS QUE SUNT IN [ASIA VIDI]T FILII HO[MINIS IN]TER VII CANDELABRA AUREA.

8

The number 8 represents rebirth through baptism, or rather resurrection and the afterlife. This is why baptisteries and baptismal fonts are often octagonal in shape. It must be said that this type of building would gradually be abandoned with the extinction, as early as the 6th-7th centuries, of baptism by immersion.

But even in the Romanesque period, octagonal baptisteries were built. A splendid example is that of Florence, dedicated to John the Baptist, the baptiser par excellence and patron saint of the city (in the figure, on the left).

But this geometric figure was also used by powerful men such as Frederick II for his 13th century Castel del Monte (in the figure on the right, a photo taken from the central courtyard). Or by the Knights Templar who were always very attached to the number 8, probably in homage to the Dome of the Rock, on the esplanade of the Temple of Jerusalem where the Templars had their headquarters.

In medieval art, just as the number 7 is rare, the number 8 is equally widespread and appears in the most diverse forms.

We often find it as an 8-petalled flower or 8-lobed palmette as we see, for example, between the paws of a centaur and a lion (images of lust and death) facing each other at the sides of, probably, Gilgamesh. The 8, symbol of eternity, here perhaps alludes to life or eternal damnation. The example is taken from a capital of the priory of Saint-Marie de Serrabonne (Pyrenees).

Eternal damnation, as clearly alluded to by the image of Satan of Saint-Pierre in Chauvigny, in western France, clutching a book or an altar stone engraved with a cross and four dots, eight symbols in all, to his chest. This represents the eternity of death and the condemnation of sin. The demons flanking him have crests with eight points on their heads, imitating the flames of hell, and they drag an old man and a young man towards Satan, symbolising the vices of the spirit and the vices of the flesh.

9

The number 9 contains three times the number of persons in the Trinity. It is a number associated with divinity, with the number of heavens, of angelic choirs, and so on.

It is also the number of the Crucifixion. In the Gospels, Jesus is crucified at the third hour, suffers agony at the sixth hour and dies at the ninth hour.

This is another reason why it is associated with the afterlife and heaven.

We often see the number 9 represented in the form of palmettes, flowers, spheres, floral scrolls, zigzag friezes and so on.

10

According to St Augustine, 10 is a perfect number because it is the sum of the first four numbers: 1+2+3+4. For this reason it is connected to the number 6. 10 is the number of the law, of the Decalogue that God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai, but also that of the strings of the psalter of King David, ancestor of Christ. With this instrument in his hand, we often see him depicted in Romanesque art: 10 strings that move the 10 celestial spheres as conceived by men of the Middle Ages, referring to Plato’s ideas.

It must be said that medieval intellectuals oscillated between a sky conceived of 10 spheres, 9 mobile ones plus the immobile empyrean, a conception supported, among others, by Michael Scotus, and a sky of 9 nine heavens, as theorised by Albertus Magnus. It is true that the concept of 9 heavens is the most widespread, also because it agrees with the angelic hierarchies of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It is not for nothing that it was the one adopted by Dante in the Divine Comedy. But the number 10 will always retain this sacred meaning that dates back to antiquity.

Finally, as a consequence of the universally diffused custom of counting on the fingers of the hand, 10 represents the sacred limit that no one is allowed to cross.

11 e 12

11 is the number of sin, because it breaks the barrier of 10, the number of the law, of the Decalogue. And sin, precisely, is the breaking of the law.

The number 12 is the product of 3 and 4 and for this reason it is also associated with the number 7, which is the sum of these two numbers. Remember that 3 is the number of heaven and eternity, while 4 is the number of earth and temporality. Their relationship produces totality and the universe in its completeness.

12 is the number of hours in the day and night, of months in the year, of zodiac signs. But also of the tribes of Israel, of the apostles and of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

The number 12 is therefore one of the fundamental numbers in the Bible and, in consideration of the number of measures and gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem of the Apocalypse, 12 to be precise, on the facades of Romanesque churches we often see arches with the apostles, sometimes associated with other figures of saints.

This is the case of Notre-Dame-la-Grande in Poitiers, whose façade has 14 arches with the 12 apostles and 2 saints.

In the aforementioned church of Saint-Pierre in Chauvigny, as in many other places, the same stripes or locks of the animals represented correspond to the symbolism of numbers.

For example, there are 12 locks of hair on a lion’s head, the tails of which are braided to form a heart. In this case, 12 is the number of the Church and its activity for the final coming of the Heavenly Jerusalem and the world finally free from evil. The man being devoured by the lion is the one who accepts the suffering imposed on his existence because of original sin. And let’s not forget that the lion is also the symbol of death. We must die in order to rise again to eternal life.

Since it is also the number of time, 12 is often represented, as 12 or its multiples, in the rose windows of cathedrals.

Here are two beautiful examples: the rose window of the Basilica of Collemaggio with 12 petals on the inside and 24 on the outside, and the rose window of Trento Cathedral with 12 petals on the ‘wheel of fortune’ representing the months or hours, associated with 4, as can be seen from the four rosettes, which could symbolise the seasons instead.